It must be two years ago, at least, that an Australian sports photographer confided he had seen a Sony prototype which would blow away everything – an Alpha which could shoot at incredible frame rates (he mentioned 15fps) and follow focus. It may have been something unlike the Alpha 77, which follows focus 12fps with locked preset exposure, or in any appropriate exposure mode at 8fps. Or it may have been an early experiment. Whatever it was, the 77 is close to this rumoured prototype .

The Alpha 77 is a successor to the Alpha 700. Here is beside my old and well-worn 700.

The viewfinder

The Alpha 77 is a camera that points the way for future development, whether of DSLT (Sony ‘Translucent’ mirror technology) or entirely mirrorless SLR-mount bodies. It’s the OLED viewfinder with 2.4 megapixels of self-illuminating RGB which changes the game. It makes the transition from optical to electronic viewfinders likely for everything except a limited choice of professional optical viewfinder DSLRs. EVFs will not be unique to Sony and it will continue to develop in resolution, colour fidelity and refresh rate.

But this type of viewfinder has a specific limitation. Unlike earlier EVFs, the Sony OLED has a threshold below which it simply turns the pixel illumination off entirely. To save battery power, this is set to a relatively high black level and clips the three-quarter tones straight to d-Max. All EVFs are slightly unsatisfactory to the human eye because there’s no real shadow detail to see if you switch your glance away from well-illuminated parts of the view. The new OLED has dead black shadows and it doesn’t matter how much your brighten it, the cutoff is based on exposure level in the image.

If you own an A55/33/35 then the new finder is so far removed it might as well be an entirely different era, not just a generation. The area surrounding the huge visual image is dead black, not milky and luminescent like the A55. The shooting information is set neatly outside the image, not overlaid at the edge overlapping picture detail. The colours are bright and the information text, though smaller to the eye, is crisper and far more legible.

One comment (added after this was first published) – the A55/33/35 may be considered better in very low light. In good light, the OLED/24 megapixel combination is excellent. In low light, it shows noise until focus and exposure are confirmed by shutter pressure, at which point the view clarifies and the noise reduces. In near darkness, its shows very strong noise, mainly red, which largely obscures any visible detail. In conditions where exposure was 15 seconds at f/2.8, ISO 100, using the A55 and A77 side by side the A55 was better. It looked grey and flat, but surprisingly detailed and bright into shadows which were too dark to penetrate by eye. The A77 gave a contrasty screen or finder image with little useful detail, nothing in the shadows, and very strong noise. Clearly the CMOS sensors are responsible for whatever level of detail is visible, and the A55 sensor seems to me have a couple of stops more lift to tones on the threshold of its sensitivity. The EVF types differ in the A55 showing more shadow detail with lower contrast, and lower colour saturation so the noise does not look bad. Bottom line, the A55 is half way to night vision; the A77 is like turning on an old UHF analogue colour TV, no signal, just noise.

There will be users who complain that having vital information just above and below the image area means they don’t see it because of their specs. But the A77 has the best eyepoint and visibility for this info of any model to date. All I can say is that if you ensure you are using the EVF correctly, you will always be in touch with what the camera is doing.

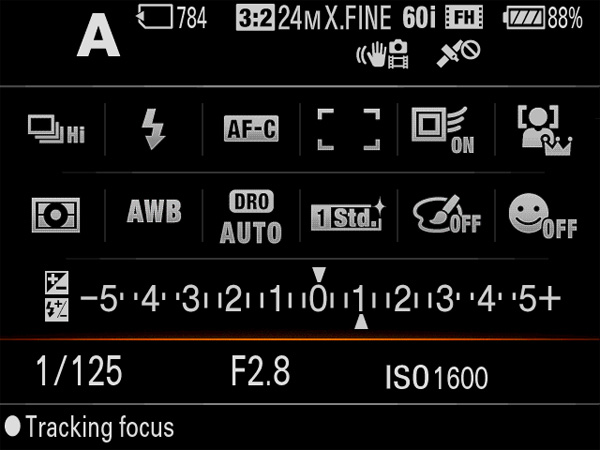

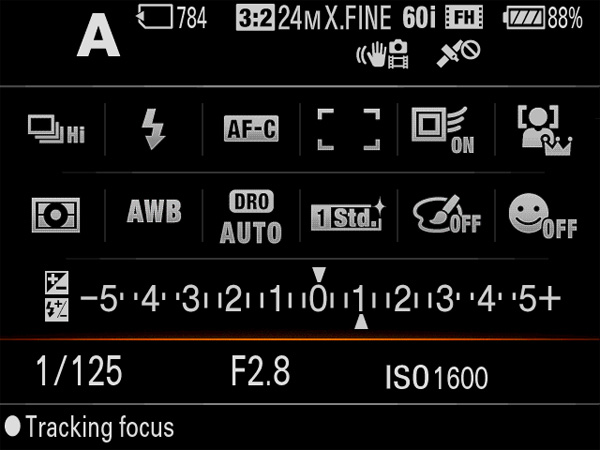

This shows a ‘busy’ finder display – in fact, everything overlaid on the photo here can be turned off leaving just the active focus point (a single one, if you use centre spot focus) and the neat information bars above and below the image area. The rest of the field is dead black too, not milky grey like the Alpha 55, and the contrast is high. This image is dropped in and has no connection to the information displayed!

The result is a very graphic view of your composition. Despite the impressive size of the apparent viewfinder image, it is not as large visually as the Alpha 900. The A700 for example is 95% field at 0.90X of a 1.5X sensor coverage, a viewfinder ‘size index’ of 0.57X (0.95X0.9/1.5). The A900 is 100% of full frame at 0.74X, index 0.74X. The A77 is 100% of 1.5X format at 1.09X, index 0.726X. It’s therefore closer to the A900 than the A700.

The A77 eyepiece glass is much closer to the eye than the A55 or previous SLR models, and the upper positioned eye-sensor turns the finder on and off with precision saving power but causing no delays.

But has Sony got the figures right? The A55 claims to be 1.1X and 100% view. Each camera has a different eyepoint – 27mm for the A77 compared to a mere 19mm for the A55 – but this should not be allowed to influence the stated apparent magnification. Placing one camera to each eye, the A77 has an almost 20% larger apparent viewfinder field (linear) than the A55 and about 30% larger than the A700. It is just a fraction smaller than the A900 as the calculations indicate.

It looks to me as if the A55/35 manual misrepresents the EVF size in that camera, it very clearly is not larger than the A77. Perhaps they include the dead space not used for the image but for data. In the A77, the data display is tight and efficient and it can show everything you ever want including the ISO in use when you select Auto ISO.

All the other figures agree. It also makes the A77 finder view an almost perfect match for Nikon’s full frame DSLRs, which have a slightly smaller apparent screen size than the A900.

The less-shadow-detailed aspect of EVF works for composition much the same way early Leica viewfinders did. The scene is simplified, and this tends to concentrate the eye on impact and simple compositions. Using the A900 alongside the A77, I was struck by the way the A900 puts you in touch with texture, colour, subtle light, and fine details. The A77 reduces the world to simpler tones and connects you to shapes, composition and impact.

As for flicker, shearing when panning, clarity of focused detail – well, these are all limitations, but much reduced in this new finder. What is not so limiting as the A55 or the earlier NEX models is the speed of startup from sleep. The A77 finder really does go to sleep (the A55 is very good at failing to switch off) and wakes up so rapidly, as your eye approaches the finder, you don’t miss the shot. Combined with the mere 1/20th second shutter lag, this SLT gets back to the responsiveness of classic non-AF SLRs.

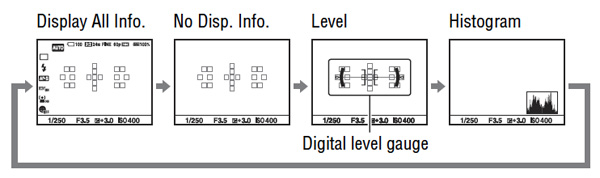

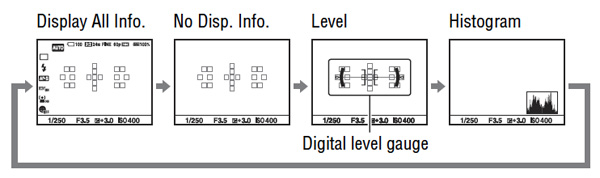

You can cycle through these displays or choose to skip one or more when pressing the Display button (there’s a menu item to configure exactly what information each press shows you, with separate settings for the EVF and the rear screen). These diagrams from the manual do not represent the finder very well. Our colour version, using a finder overlay file supplied by Sony, gives an accurate view of what looking through an A77 finder is like.

Here I am, I’ve written stacks about the viewfinder and not even begun to describe it fully. Tell you what – go and find one, try it. I can’t photograph it adequately (I have tried) and it would be exhaustive to go through the deep menu settings of the A77 which let you decide for example how many different information-display setups you scroll through when you press the Display button. Don’t want EVER to see the horizon level guage? Then set the camera to skip it. Hate the graphic display of f-number and shutter speed scales against each other? Deselect that too.

From the Alpha 77 Karma Sutra – left, position for portrait photography; right, position for those who like to video themselves and still look as if they are in eye contact with the viewer.

And then there’s the rear screen. It has a double hinge and rotate action, of which more later. It is a top grade screen, 3 inches and nearly a megapixel. If you plug an HDMI monitor in to the camera, that will take over providing a better solution for studio or video previewing. Even a 20 inch or larger HDTV set looks sharp when fed from the Alpha 77.

The menus of the A77 require the attention to website presentation detail best reserved for the galley-slaves* of dPreview. Trust me, if there’s anything which can be set on any other Alpha, it’s probably settable on the 77 or not there at all. I’m sad to see that I can only control my auto ISO range minimum between 100 and 12800, and my maximum between… 100 and 12800! Of course this is great. I can have auto ISO over any possible sensible range but not ISO 50.

*Queried on dPreview forums – I’m an ex-newspaperman. Galleys are proofs of type (or the metal itself) and if you’ve ever worked on the TV listings or the Sports pages, you’ll know what it means to be a galley-slave in editorial terms – form before function, and function before fun! Well, I can have fun. I do not have to reproduce every single screen and menu because there’s no big boss saying that’s how it is done! It’s great work that dPreview undertake. But as someone else has already done it, I prefer to spend my energy doing the stuff they haven’t done. Then you can read both.

ISO 50? What use is that, with less dynamic range than 100?* It’s a great deal of use. In my studio with powerful flash – which this camera can cope with perfectly, having a setting to over-ride exposure simulation in the EVF/screen and do auto gain for modelling lights – it gives me an extra stop instead of being forced to work at a setting like f/13 or get overexposure. Outdoors in bright light it combines with the 1/8,000th top shutter speed to remove the need for a 4X ND filter to get superwide apertures, but due to reduced dynamic range, it’ll still clip whatever highlight would have been clipped with an overexposed ISO 100 shot. In the studio I can control my contrast to use it well.

*This is Sony’s own statement in the manual, page 139: “The recordable range of the brightness of a subject (dynamic range) is slightly narrower for areas where ISO is less than 100.”. DxO Labs tests actually say that colour depth, tone depth, dynamic range and signal to noise ratio are all at their best if you set ISO 50, but they also show that ISO 50 is really ISO 63 overexposed a bit and ISO 100 is really ISO 80 underexposed a bit. Where that leaves the intermediate 64 and 80 settings on the camera we can only guess.

As well as all the info in the finder and on the back LCD, you get this top plate LCD which means you can close the back one. Even when the camera is asleep (power save mode) the sensor must still be receiving and handling the image, as the exposure display will change when you move the camera around. I’d guess this is a low power mode which also enables the system to continue to monitor exposure between frames during sequence shooting.

At first I did not fall in love with the Alpha 77 – when my purchased firmware 1.02 version body locked up on me in front of one Canon and one Nikon user I was just a little angry with it. It could have done this somewhere quiet, on its own, without spectators. Even now with firmware 1.03 I am not sure it won’t repeat the cataleptic fit, but it shows no signs of doing so. See my section on the Movie mode later on, though…

The SLT mirror and ghosting

I’ve tested the Alpha 77 in the most demanding lighting conditions. Sony says the SLT mirror (a very thin film of plastic stretched on a frame) has new mirror and antireflection coatings. They have also paid extra attention to the design of the AF module and the interior of the darkchamber, to avoid reflections.

Though some colour fringes on the bright water definitely hit this 16-80mm CZ shot (along with a colour bokeh issue making those in the foreground magenta and those to the rear greenish) there was no hint of any ghosts or flare in dozens of shots taken in conditions like this.

This light is extreme, and the patches of sun and reflection are placed exactly where the Alpha 55 tended to produce flare. The Alpha 77 shows no sign of it, and has not in any of our photographs so far.

As far as loss of sharpness goes, I do not believe there is any more significant sharpness loss from the SLT pellicle than there is from, for example, the rear filter permanently fitted into a 300mm f/2.8 Apo G tele. Both are between the lens and the sensor and both are plane clear optical elements. If anything the glass thickness and distinct double air to glass surfaces of a rear mounted filter make it far more likely to degrade an image than the SLT. Almost any filter you fit in front of the lens is going to have a greater effect (unless you spend a stack of money, a really bad effect on 24 megapixels – we’ve replaced our older Minolta, pre-digital Hoya and other filters with the latest Sigma EX DG after testing them).

This is just a routine test I ran at all ISO settings to check colour and tonal response. Not noise. I already knew before doing this that the noise thing was a non-issue for the simple reason that this sensor beats anything else out there; I’ll start pixel-peeping for noise when another maker comes along and shows they can do this pixel density better. The colour is also very consistent indeed across the ISO range and the feathers in the mask retain the expected detail up to ISO 3200.

This picture was taken using a setting I quickly discovered is just perfect for news, PR, presentations and images needed quickly from events – the Small JPEG in camera, with DRO enabled, at ISO 3200. Sampling down to one quarter of the file size (still large enough for an A4 print) creates a dead sharp, low noise image. Photographers do some good, occasionally – this is a cheque for £3000 being presented to DJ Dave Lee Travis for the PACE Centre charity, by the Master Photographers Association. Their annual dinner happened just a week after I got my Alpha 77. I was confident enough to risk taking all my press and PR shots on the new camera.

And this is a 100% pixel level view of that shot without any post processing.

Input and feedback

Then again, having to set up the camera and realising the full extent of the customisation possible through the Menu and Fn buttons, I felt depressed. This was almost like handling a Canon 7D – one of those cameras where, if someone passes it to you, you can never be sure if it has been configured only for photographing flocks of ibis flying behind bare poplar trees. Would its 19 AF points and 11 cross type sensors do the 7D trick of locking on to a sweet wrapper someone dropped on the lawn instead of the wedding group a yard further away?

Well, yes. The A77 can do that sort of wrong stuff if left on wide area focus – but it doesn’t light up the wrong AF points in the finder to fool you, and it does not require programming of AF preferences to avoid proximity or response speed errors (both Canon and Nikon pro models can disappoint if used ‘out of the box’, and need their defaults changing depending on your typical photo situations). Instead, if provides very accurate feedback about which sensors are being used. And it has Face Detection which really works, because this is a live view camera 100%. I have never liked Face Detection much until the SLT EVF generation arrived. Even then, not much.

Face detection kept the focus on photographer Paul Cooper (right) accepting the president’s ribbon of the MPA from Henk van Kooten (left) despite Henk’s focus-target jacket moving into the foreground of the AF zones. Taken by stage lights at ISO 3200

I had to take a few shots where a person receiving a presentation was facing the camera, and the presenter often stepped into shot with back of head to the lens. With Face Detection on, the A77 never once switched focus to the nearer person, and always stayed locked on to the subject facing me. This is a situation where the above-mentioned makes, if allowed to use wide area or multi point AF, tend to shift focus to the foreground intruder because as conventional DSLRs they don’t have Face Detection in optical viewfinder mode.

The auto exposure of the A77 seems to be more closely linked to active AF points than any previous model. It may have 1,200 metering zones on the CMOS sensor but it will bias strongly towards correct exposure at the point or points of focus, especially if the central point coincides with a very bright are. I do not mean it is literally spot metering. I mean that, for example, in my office with medium lighting and a very bright computer screen if the camera is aimed at the screen the exposure in matrix mode, with centre spot focus, becomes correct for the screen and the rest dark. When the screen is moved away from the centre zone, exposure increases by two stops even though the overall image contains about the same brightness.

What I’m seeing may not be the same sort of meter-linking-to-AF that is found in the Canon EOS 400D, as an example. This will give you over or under exposure if the focus point hits a dark or light area. The A77 biases towards avoiding overexposure. A dark subject at the central focus point does not seem to brighten the image the same way a very light subject, like a screen, darkens it.

This is not like separate metering cell TTL, the classic Minolta honeycomb. It isn’t even like a camera with centre weighted or spot optically fed meter cells. Every point on the sensor is a spot meter even though you can only ‘spot meter’ from the centre. Every point is equally sensitive down to EV–2 (ISO 100 with f/1.4 lens) and up to EV17. It is four times more sensitive as a matrix/centre-weighted meter than the Alpha 900 and a staggering 16 times more sensitive than A900 spot metering mode. It also has +5 to -5 EV exposure compensation compared to the A700’s+/-3EV (A900 – 3EV, expanded to 5EV by later firmware, but the 700 was never improved – see comments, originally I referred to A900 as 3EV either way, as that’s in the manual). And whatever things the SLT mirror does, it seems to feed the new AF module plenty of light – it’s able to focus in conditions half as bright as the A900. Added comment: the A77 metering is four times as sensitive as the new Canon D1 X, so although that camera has amazing sensitivity up to ISO 204,800 the A77 will actually meter exposure in lower light.

So, after a couple of weeks, I began to realise that the A77 was giving an even lower failure-rate than the A55. I had learned which settings to prefer – three zone focus for example is far better than old-style wide area and almost makes single centre spot focus redundant. I was finding that exposure is generous but never highlight-clipped, because it’s read from the actual imaging sensor; you can trust the simulation given by the EVF, too, and adust the +/- over-ride with confidence.

The camera stopped being complex and started to suit my declining mental powers. Life is a curve. You start just learning to set shutter, aperture and focus. In your prime, you want to set twenty different things for every shot and switch from P to A to S to M with C or S or A and -2 sharpness and ten stop HDR then portrait look for the next one. Ultimately as the brain cells sneak off for a nap you find good old shutter speed, aperture and focus do you just fine.

If you need reminding in big print, let the rear LCD see the light of day, and you get this big clear information pane on demand.

Now some cameras have fooled me, there are no dials and they just hid this stuff from me so I’d end up with bad things like the optically soft set of landscape pix I shot at 1/2000th and f/5.6 (wide open) on the NEX-5 last month. But the Alpha 77 with its top plate LCD info display, its ‘come to life’ burst of finder shooting information when you take first shutter pressure and confirm focus – well, it is constantly reminding me what I am doing. I know other cameras and other Alphas have finder displays, even the NEX was probably telling my longsighted eyes what it was up to, but the Alpha 77 presents working information better than any camera I’ve used. It is simply a very clear and well designed display both in-camera and on the rear screen.

If you enable image review, the SLT cameras slow down. I fold the rear screen to face the camera back. I have turned off image review. I shoot with confidence just as I would once have done on film and sometimes I do not check a single image until I’ve copied the card contents to my computer.

Button pushing

The Alpha 77 has loads of buttons despite Sony’s one-time insistence that they planned to have fewer mechanical components in future. There are nine push buttons, one rocker button and one control wheel on the back of the camera alone; five push buttons, one collar switch, one shutter and control wheel on the RH top. Then there’s the stray stop-down button, the lens change release and the AF-mode switch living round the mount.

Rear screen folded away and protected – that’s how I use the camera all the time. Plenty of buttons to push – and you can have fun swapping their functions round to confuse your friends!

Several of these buttons can have their functions modified so they no longer do what it says on the silkscreened white or blue print (white for shooting mode, blue for playback). If you are particularly odd you can even swap round functions and confuse people who borrow your camera (shades of Canon!). If you are relatively normal you can leave this well alone. You may customise the stop-down preview button to show the final picture effect instead (stop-down plus picture style and shutter speed result) and through the menus you can change the behaviour of lens-resident Focus Hold. The instruction manual omits to mention these are on the lens, and not on all lenses – some owners have spent ages looking for the Focus Hold button which does not exist on the camera.

What’s most odd about the A77 is that three of the main dedicated-function buttons are completely interchangeable. ISO (next to the shutter) AEL and AF/MF (under your thumb) can all be changed to do anything from the following long list of functions:

AEL Hold*

AEL Toggle*

Spot Meter with AEL Hold*

Spot Meter with AEL Toggle*

AF/MF Control Hold*

AF/MF Control Toggle*

Object Tracking

AF Lock*

Aperture Preview (stop down)*

Shot Result Preview (final picture simulation)*

Smart Teleconverter*

Focus Magnifier*

Memory

Exposure Compensation*

Drive Mode*

Flash Mode

AF Area

Face Detection

Smile Shutter

ISO*

Metering Mode

Flash Compensation

White Balance*

DRO/Auto HDR

Creative Style

Picture Effect

Image Size

Quality

*The entries I’ve marked with an asterisk already have their own dedicated buttons for which these are normal function choices (AEL button, for example, covers all the first four but can only do one function, preset in menus).

There is one button you may want to modify if you own lenses with a Focus Hold button. The AF/MF button, by default, performs this function with most lenses (it switches to MF when pressed, the same effect as holding focus). So it’s almost a spare button, given that there’s also an AF/MF switch on SSM/SAM lenses and a body AF/MF/S/A/C switch too. Since it sits right next to the AEL button and closest to the rear control wheel, it a natural choice for any function you might want to use in a hurry.

You can not change the function of the Finder/LCD manual switch button, the Drive Mode, the White Balance or the Exposure Override. You can switch the Preview and Smart Teleconverter buttons between two functions each only. The Fn button accesses all the parameters you can’t reach directly through any custom button (like setting the Auto ISO range) and most that you can (like Face Detection). Its full function list is:

Memory Recall (only present when mode dial set to MR)

Scene Selection (only present when mode dial set to SCN)

Movie (only present when mode dial set to Movie)

Drive Mode

Flash Mode

AF Area

Object Tracking

Face Detection

Smile Shutter

ISO and ISO Auto setup

Metering Mode

Flash Compensation

White Balance

DRO/Auto HDR

Creative Style

Picture Effect (only active for JPEG-only shooting)

The Display button can not be customised and only serves to cycle through Display setups – but you can customise those, and thus what the button does for you (above, Menu to set which finder display states you wish to cycle through, ticked). The Help (?) button can also not be customised, which if you don’t want potted hints and tips makes it redundant in shooting mode, though it serves as the Trash button when reviewing images. The Playback also can’t be customised, nor can the Menu button (which can return to Last Used or Top by setting a preference), nor the top LCD illuminator button. This one is interesting because it toggles – the panel light remains on until the camera goes to sleep, or it’s pressed again to turn off.

In use, I found there was one button missing which would make a huge difference to this camera. The 12fps ultra high speed shooting mode is only accessible through the mode dial. Because of the way the camera handles bursts of frames and buffering, it would be useful to be able to shoot normally in any mode (single frame, or other continuous speed) and switch to 12fps by holding down or toggling a button (preferably holding down, say, the AF/MF lock reassigned for this purpose).

Here’s a neat touch – as long as you have a lens with no MF/AF switch on it, you can set M focus on the body selector, and pressing the AF/MF button will do autofocus for you, letting it go will lock the focus back to manual. That’s another reason to like my 16-80mm CZ on the A77 – ideal for studio products or architecture, or indeed for landscape. It does not work with the 18-55mm SAM. There is in fact a bit of an overall mess with SAM, SSM, and standard lens focus types including the assignable DMF (direct manual focus) to the AF-A mode. There are some lenses where you are warned never to use body MF setting always only to use the lens switch. What you will find is that some menu items are greyed out, and some buttons don’t work, if a mismatched combination is set.

Lens compatibility

The new 16-50mm f/2.8 is enabled for in-camera lens corrections

This leads to the general question of lenses and the A77 generation. It seems there’s some additional information chipped into some but not all lenses which enables the Lens Correction function (Vignetting, Chromatic Aberration and Distortion) for in-camera JPEGs. Raw files are unaffected, and I don’t know if this information is used to enable better panoramas but that would be a practical fringe benefit. But since the 18-55mm SAM, 55-200mm mk2 SAM, and 18-250mm (an old design relatively) are in the release firmware along with the 16-50mm SSM maybe there’s no info in the lenses themselves, and future firmware will add more.

The oddest incompatibility is the manual’s statement that Front Curtain Shutter should not be set on ON for ‘Konica Minolta’ lenses (added note – see Comments at the end of this article, some discussion of this). First of all, the description of Front Curtain Shutter is misleading. When this is set to ON, it means NO front curtain shutter – electronic gating instead. When it is off, you are using the physical Front Curtain, the blades uncover the sensor to start the exposure. The manual does make it clear that by Front Curtain Shutter Sony means No Front Curtain Shutter.

But what is a Konica Minolta lens? There are very few, nearly all were made by Tamron. Konica Minolta never even got round to rebranding the Apo G lenses, they just changed the box and the lens cap and left Minolta as the name on the lens. I have a 28-75mm Konica Minolta, a 17-35mm Konica Minolta and at one point I had an 18-200mm, and of course, the kit 18-70mm and various horrible full frame plastic lenses like the 28-100mm. I think there are 75-300mms in KM guise.

Everything else prior to Sony was Minolta because KM simply never made any, or if they did, it amounted to no more than a box label change. To confuse things, some of these Konica Minolta like the 18-70mm, 18-200mm and 75-300mm became Sony lenses without a single substantial change. And many Minolta lenses became Sony lenses while retaining a heritage right back to pre-D days or the origins of the AF system itself. The 28mm f/2.8 is the most obvious example, the 50mm f/1.4 another.

Why would an electronic front curtain produce overexposure or inconsistent exposure only with Konica Minolta lenses? Given the very fast response time (1/20th of a second) and high speed of the system (1/250th flash sync, 1/8,000th shutter) the only thing I can think of would be the speed of aperture closing action. It is also something which would be invisible in revised lenses; maybe the Sony 18-70mm kit lens actually has aperture blades which close 50 milliseconds sooner than the KM equivalent.

This would also mean earlier Minolta lenses, not just KM, might produce overexposure (aperture still not fully closed when exposure commences) or uneven exposure (aperture continues to close down during part of the electronic progressive gate-opening). The same would apply to many third party lenses.

I’m pretty sure this is why the warning is made, and that singling out Konica Minolta lenses is an error. Any one individual lens may have sluggish diaphragm, indeed a common cause of overexposure in all A-mount lenses is incomplete stop-down. So the advice should be don’t use ‘Front Curtain Shutter’ set to ON with anything except Sony A-mount lenses – or test your independent lens before use.

A warning about not setting Micro AF adjustment with third party lenses is given, as usual. This is because the makers borrow lens identity codes. The Sigma 12-24mm f/4.5-5.6 Mk1 has the same code as the Minolta/KM 28-80mm kit lens. This issue will also affect the behaviour of the Auto Lens Correction register, which in our body does not have any effect on the CZ 16-80mm for example but does correct the new 16-50mm. I would guess ‘correctable’ lenses have extra information, older and third party lens won’t. So don’t bank on this function fixing JPEGs from your ‘heritage’ of early Sony glass!

Sigma has issued a list of lenses which are known to have AF problems with the Alpha 77/65, and will upgrade them free of charge. You can read the list here: http://www.sigma-photo.co.jp/english/news/info_111014.htm. It includes the 18-250mm HSM OS, which we have. Ours does not seem to have any issues at all on our A77 with firmware 1.03. I’ve also tested the 8-16mm and 100-300mm OS, 70mm macro and 70-200mm f/2.8 HSM Macro MkII. These are not in the warning list and all seem to work well, even though they do not work reliably with the Alpha 55.

The A77 has Fast/Slow AF options and I’ve used Fast. The accuracy of the AF is much better than any previous Alpha model.

Autofocus and exposure

The 19-sensor, 11-cross AF module is not most densely populated – the A900 has 10 extra hidden ‘tracking assist’ line sensors bringing it up the same total (they are there, they just don’t have screen markings) and its central double cross sensor is technically the best type around. But having eleven cross sensors does more good in practice.

AF has a new mode, Zone. This creates three groups of sensors left centre and right which act like mini wide zones. Wide Area focus can, of course, locate widely spaced details which are concurrently in focus. Zone identifies the zone with the most focused points, then works within this area. It can use information about the change in confirmed focus within one zone to help track the subject into the next zone. It also gets the exposure right more of the time.

Because the sensor is feeding image data to an analysing computer, Face Recognition and Object Tracking can be linked to the AF. There must be some theoretical speed penalty – something must be slowed down by microseconds if you enable these functions. I can’t detect it. The only slowdown is the time you take to press the central controller button to register an subject for tracking. Smile Shutter is also possible. My subjects normally scowl so I don’t use this.

The focus point – here, centre focus spot aimed first at the family and then held using the shutter release to recompose the scene – helps determine exposure. The 1200-zone metering has correctly placed the baby’s white clothes in the value range 250 to 254 RGB.

The most reliable and accurate focusing method remains central single spot focus, or local selectable single spot. Now that all of these are cross-type, there is no compulsion to stick with the centre and recompose, but it’s a habit hard to lose. I have already observed that the metering in spot mode is 16 times more sensitive than spot metering in the 900, and I would guess that when the system biases matrix metering values to the centre focus point, there’s a related gain if not that much. There is a proper near-IR AF illuminator in the camera body – Minolta tradition lives on! Without flash, it really is possble to focus in the dark and the EVF does a very grainy but usable job as a night vision viewer too. The illuminator also enables focusing on plain surfaces as it projects a pattern.

The SLT mirror of the 77 diverts 30% of light to the AF module, but this is actually more than the old semisilvered patch and double mirror system used to let through in SLRs. The AF sensor itself may not be any more sensitive, it’s simply getting a much better image feed. This 30%, by the way, means the light reaching the sensor is reduced not by the 1/3rd to 1/2 a stop sometimes mentioned, but by .6 of a stop or nearly 2/3rds of a stop. 50% would be one stop. (See comments at the end of the article for some more precise figures on the mirror split provided by Dr Daniel Oi).

My experience so far with the camera indicates that exposure is very reliable over the entire EV range. I simply leave it on the matrix multi-zone setting. The EVF warns me if it’s going to bias too much to the focus point.

High speed shooting

This brings me to the aspect of high speed sequences. No cameras in this class has ever achieved 12fps, let alone at 24 megapixels. In theory you get 13 raw or 11 RAW+JPEG frames before the camera slows down, and it looks as if the buffer must hold about 320MB. The camera does not have a dual processor like the Alpha 900, and it does not benefit from the robust performance of fast CF cards.

Autofocus is provided in Hi drive mode, along with AE (8fps, accessed via the Drive function button, in any shooting mode). Using this shooting speed you have full control.

In Speed Priority AE mode (the 12fps setting on the mode dial) the focus is locked before frame 1 if you have the camera set to Single (S) AF, but in exchange for this, you can set both the ISO and the aperture. You can also set these if you use Manual focus.

If you set the focus mode to C (Continuous) then both AE and AF continue during shooting. You can set the ISO, but not the aperture, so the ISO is your only way control the shutter speed. Added note: the Canon 1D X has now bettered this record high speed shooting by providing 14fps. This mode in the Canon locks both AE and Focus with the first frame, locks the mirror up, and you must use Live View on the rear screen to compose the shot. For focus tracking with viewfinder, the 1D X is limited to 12fps.

12fps is very impressive. It makes a huge difference in action work. I often test sequence shooting on the local races, and I quickly found that even tracking a horse (necessary to keep it in the frame at all for more than one shot at 3fps) certain frame rates just produced two stages in its stride, repeated. The horse was galloping at 2.5 clops per second and I was shooting at 5fps. With 7fps it gets better, 8fps or 10fps still better and with 12 fps you reach the point where four different positions of the legs are recorded.

Also, it becomes possible to aim the camera at a fixed spot like a hurdle, and fire, capturing several positions of the horse before it leaves the field of view. It is not as necessary to pan with the subject every time to get more than one shot.

Animation of three hand-held frames, cropped from a Sigma 70-200mm shot taken at 70mm, showing how 12fps captures very fast action in relatively small steps. At 5fps, the second frame would have the horse leaving the right-hand edge.

In practice, you certainly get your 13 raw or 11 R+J shots at 12fps or the slower AF-capable Hi 8fps setting – or indeed at the slower 3fps rate. But you don’t get anything like the same continuous shooting capability as past models even if you knock the JPEG size right down. You’ll get around 18 Normal Small JPEGs (6 megapixels, lowest quality) at 10 to 12fps before the rate slows down to an erratic 3fps with occasional half to one second pauses. For raw files, after your 13-ish burst is up, you may get between 0.5 and 1 frame per second with occasional one to two second pauses. With an average SD card (20MB/s write) you will wait 15-20 seconds after the last shot before being able to shoot fast bursts again.

Here’s another sequence, this time as stills without the annoying animation you can’t turn off 🙂

And here, below, is a 100% crop from the original ISO 800 raw file processed using Adobe Camera Raw 6.5 (Sharpness 50, Radius 0.5, Detail 0, Masking 0; Luminance NR 25, Luminance Detail 50, same from Chroma NR)

Sharpness? The 12fps C-AF setting forced the Sigma 70-200mm to be at f/3.5, two thirds of a stop down from full aperture, but also gave a shutter speed of 1/6400th. I could have perhaps picked another detail with slightly more punch, and looking at all the shots, my prefocused point was actually about 1 metre behind the horse (if the AF refocused during this sequence, I can’t see any evidence in the images). The 8fps or Single-Shot AF 12fps settings allow control of aperture, and I know that f/5.6 would have cleaned up. Just remember you are looking at a section of an image something between 6ft and 8ft wide, it’s very easy to view a tiny clip like this as if it was just another digital image.

I tried one technique, shoot 2, 3, 4, 6 frames with brief pauses – as if catching different moments of an event, in bursts. Even though I spread the 10fps bursts over a ten second interval, by the time I had totalled 20 raw frames I was down to the single shot per second or worse situation.

To follow up, I shot a burst then allowed the buffer to write for about 8 seconds before firing again. I got seven frames at 12fps, which fits in with the card in use taking about 15 seconds to finish writing from a 13-frame burst.

For one of the horse racing tests, I shot one burst of frames and as the camera slowed down, two horses fell and two jockeys were injured, one requiring a stretcher. I was unable to get ANY pictures of the incident as it happened, and by the time the Alpha 77 was able to shoot again, the ambulance crew was on the track. Each race gave me just two chances to shoot a burst so I’m afraid that testing every single setting combination on the camera was not possible.

Panorama speed mystery

There’s something I don’t understand about the raw, file and buffer handling of the Alpha 77. Shooting panoramas – which have to start with exactly the same frame by frame 24 megapixel data readout – I counted 42 frames apparently firing at something close to the 12fps maximum, then creating a panoramic JPEG, and the finished 6.7MB JPEG file was written to card and the buffer cleared before I had time to see if the light was still on.

What exactly is happening here? How could the processor and the buffer somehow handle the throughput of the wide panorama with at least double the number of continuous burst frames I could get with even the smallest JPEG – and then do all the computing to assemble the panorama and write it to card, leaving me ready to shoot immediately?

I ask this because when shooting panoramas with the Alpha 55, my 15MB/s SanDisk Ultra II SD card failed – it was not fast enough, could not handle the data and became corrupted. Clearly panorama shooting is data intensive one way or another. But in the Alpha 77 it appears to be allocated buffer and processing power which is denied to more useful motordrive sequence shooting.

Movie shooting does not enjoy the same fast buffer clearing. Shoot any higher quality movie beyond a mere blip on the button, and you can’t fire a still frame for some seconds. With some HD-movie systems, you actually shot a still frame during the movie and lose nothing except a couple of movie frames; with others, you can end the movie by pressing the shutter and capturing a still. In yet other makes, you can shoot a still but lose two seconds during the movie. All these solutions are valuable when still shots could be important. The A77 movie function does not permit any such choice and may block all shooting by occupying the buffer to card writing process for many seconds.

And, in reverse, you can not initiate a movie while the card write light is on. I tried this with one of my horse race test subjects. I decided I would shoot the front runners going over a hurdle, get my 12fps burst, then do a few seconds of movie of the stragglers who reach the spot a few seconds later. Although I could have shot further (faltering) still frames, movie shooting was blocked out with a warning message telling me ‘Writing to Memory Card – Unable to Operate’. When raw shooting was set, this lasted many seconds, but interestingly with the small JPEG option only two or three seconds were blocked out.

After my tests of the high speed shooting functions, I conclude that to cover some sports events well you would need a pair of Alpha 77s, or the 77 and some other camera – and you would need to keep a close eye on the card writing light. As a result of the performance with my SD cards giving write speeds around 20-30MB/s I ordered a SanDisk 45MB/s Extreme Pro, and plan to get a 95MB/s card when they are available.

Added after receiving the SanDisk Extreme Pro 16GB 45MB/s card: burst shooting is not extended, using raw it varies from capturing 10 to 12 raw frames at maximum rate, sometimes with a single frame jumped (two groups of 5-6 frames) which never happens with my ordinary Transcend 20MB/s card. Buffer to card writing is reduced to around 10 seconds from around 20, but at least with this extra card speed, there is no way to extend the approximate 1 second unbroken raw shooting burst.

The Alpha 65 and 77 are the only DSLR/T cameras so far made which use the USH-1 SDXC specifiction to allow writing data at this kind of rate. They are ahead of the card game. But they need to have this capability. Anyone expecting to make full use of the high speed drive functions and best video quality of the 77 with cards like the faithful wallet full of Transcend 16GB Class 10s we have been using will be disappointed.

The dedicated Movie mode

On the mode dial of the A77 there is a movie position. This does not mean it has changed, like some Canon models, to be incapable of shooting unplanned movie clips – you can do this at the press of a button, like other Sony models. What the Movie icon means is that you gain access to manual control of ISO, shutter and aperture. As a penalty, you lose AF.

Why? That is easy to answer. The AF sensors in the 77 are rated for f/5.6 aperture use. Default movie apertures range between f/3.5 (typically set on fast lenses) and f/6.3 (well, with an f/6.3 zoom lens there is little choice). AF works best in this range. If you really want to shoot AF movies at f/2.8 on a 200mm lens, try by all means. I have tried at f/3.5 and for every clip which has a smooth focus transition, there will be another where the SSM, SAM, HSM or plain old screw drive makes a sudden shift.

So if you want to work at f/1.4, leaving focus to AF would be a disaster. Apart from making constant shifts, there’s a big chance of hunting. I worked with the 24mm f/2 SSM Carl Zeiss for a while, and this lens does not find focus easily in low light with any camera. On the A77 for video it was auto-set to between f/2.8 and f/4 in low light. Video AF happens at the actual working aperture, not wide open like still AF. Being stopped down a little improved the 24mm’s accuracy.

And if you want to work at a smaller aperture than f/6.3 – say f/16 for a deep focus effect with a superwide lens – then AF simply would not work at all. The Manual Focus restriction placed by using the Manual Movie mode is necessary despite the howls of protest it’s produced from those who don’t understand the technology involved. A side benefit of setting Movie mode on the dial is that your view through the finder is cropped correctly to the HD area before you start filming, which makes composition easier – see below.

In the Movie position on the Mode dial you might believe you can use the self-timer. The manual ticks that box. We had to check it, but although you can set the Drive state, including self-timer, doing so has no effect on Movie shooting. Nor can you shoot stills with the Mode dial in this position. Various other manual details, such as indicating flash can be usedin this mode, are also incorrect or there’s a small firmware glitch with the camera. I would expect the shutter release to be operational with the mode dial set to Movie, so that stills could be captured. It is disabled and you can’t take still shots at all if the dial is in this position. Be warned!

Not only that, but after I had pressed the Self Timer 10 second setting when in Movie mode, the LCD top display showed a single frame symbol plus the 10 from the self-timer mode, and the shutter release was disabled even after returning the mode dial to Program or other settings. The Drive mode had to be reset to get it out of this tangle.

As for the instant Movie button, it’s not in the best place – a long thumb reach for on and off actions to start and end clips and the placing tends to make me tilt or move the camera needlessly. When adjusting the viewfinder dioptre to switch from working with spectacles to working without, it’s so close to the dioptre control I push it occasionally by mistake. I would like the Movie mode to switch operation to the main shutter release OR the movie button.

It’s worth noting that picture effects (see later pages) can be applied to movies, as can all other image adjustments, and will be seen in the finder as you shoot.

But what you won’t see until the moment you press the movie button is the working HD movie area. It is a surprisingly fierce crop from the full sensor, not just a top and bottom slice to HD 16:9 format. This is required for the Steady Shot digital, pixel-shift based movie stabilization which does not move the sensor like regular SS. It reduces the 1.5X area to something like a 1.8X area, not as much ‘zoom in’ as using the 1.4X smart converter but enough to cut heads and feet off subjects you have pre-composed using the full finder. There are indicator marks on the display, that’s true, but you will find them hard to see in many conditions even if you remember to use them.

Shot with the 24mm f/2 lens – no way to move back or zoom out for the movie, but plenty of space you would think for the 16:9 HD crop.

This is what the HD movie viewfinder field switches to when the Movie button is pressed (slightly re-composed horizontally but not cropped at all). The movie stabilization need the surrounding pixels. It highly effective, both through the live viewfinder and when viewing the results, and totally silent unlike sensor-shift SS. It also does not warm the sensor assembly up as much.

A caveat to movie shooters. Select the highest quality AVCHD 2.0 formats (the camera will warn you) and you may not be able to play them, burn them to disc other than Blu-Ray, or import them into HD movie editing with programs like Apple iMovie. No doubt this will change with updates, but right now apart from Sony’s PC-only Picture Motion Browser (they have now had half a decade to port it to Mac) there are few programs which can recognise the 1080/50 or 60p 28Mbps format and even fewer which edit it. You will need to buy software to do so. On my system, Toast Titanium 11 includes Roxio HD viewer and because it is a Blu-Ray compatible disc authoring package, this was able to handle the .MTS files in all formats, and convert them to formats editable using iMovie. Roxio offers similar PC utilities.

Sony PMB is also very useful for GPS data handling, map viewing and correcting GPS data. While Adobe Bridge with the GPS Panel (download from Adobe) installed allows viewing and editing of co-ordinates, it still has no link to Google Maps, Microsoft Virtual Earth, or any other useful location display.

Sound

There is no provision for audio notes or audio only recording, which is a bit of a waste of built-in functions as this would be possible and can be useful. Audio notations attached to images are popular with travellers and journalists.

The stereo sound is not much different to the NEX or Alpha 55 despite being capable of 48kHz (better than CD) sampling. The microphone under its unusual top grille seems less prone to wind noise than most DSLRs; the wind noise reduction feature, a bass cut filter, is additionally effective. Body handling noise is present, so is lens focus noise.

The external mic socket provides 5v phantom power for popular condensor mics, and is stereo too. No provision for fixed gain is made – auto level or gain is always on. The camera needs an option to disable auto gain so that a preamp or mic with dB cut choices can be used to control a fixed sound level; better would be three levels, like Nikon; even better still a proper sound level monitor display and full control in fine steps like Canon. Without at least one of these options the Alpha 77 can not considered for semi-pro or professional live sound video work.

GPS Data

While I think that the GPS on the A77 has so far proved faster in locking and more accurate in positioning than the A55, it’s hard to quantify as I have not used both together for long enough in difficult locations. To improve your GPS, download this file:

http://control.d-imaging.sony.co.jp/GPS/assistme.dat

Create a folder on your SD card inside the PRIVATE/SONY directory and call it GPS. Copy this file into it, put the card in your camera, switch on. Go to GPS in the main menus and make sure it’s turned on, then look at the GPS ASSIST entry and you will find the assist data starts on the day you download and lasts a month. Visit the assist.dat download once a month or more often to keep your GPS working with the fastest and most accurate lockon and co-ordinates. Do not worry if you format or change cards, once in the camera the assist.dat file is copied to internal GPS memory. Your original card does not have to be present.

Sony state 15 seconds or more to acquire or change position, and variable accuracy due to GPS being a US military provision which can be subject to deliberate degrading. In this model, when no GPS signal can be detected on power up, the camera simply turns off GPS embedding (on the A55, it uses the last co-ordinate). But if you are out and about, the last position may be shown on some pictures. I don’t think I move that far in 15 seconds

.

.

An example of GPS map location from Media Pro and Google Maps – click on the image for a full size screen shot.

Adobe gripe – it’s long overdue for Bridge to have a GPS map function when Lightroom does. As it happens I use Media Pro for all my digital asset management. When this was Microsoft Expression Media 2 it has its own Virtual Earth window, but now it’s been taken over by Phase One, that has been replaced by auto-opening a web browser Google Earth window. I don’t really need to see maps at raw file stage, but it could help with filenames. I like my filenames to be a ‘catchline’ format – an alphanumeric string which contains a key word about the subject. That could be simple like venice2011-15.jpg or a bit more precise like guideccasangiorgiovenice2011-15.jpg.

Mouthful? Not ISO compliant? Not ancient PC friendly? Sure. But very useful indeed many years later when searching for stuff. And access to GPS map location helps me decide filenames, then later on input metadata for caption, keywords, description, and much more. With 15,000 finished images stored on my system everything which helps me identify them is valuable.

Image formats and styling

The Alpha 77 has a stack of great functions and features I will never use. That’s because they are not available if you shoot either RAW or RAW+JPEG. They include multi-shot modes (combining tonal range for HDR, or reducing noise for low light and high ISO) and in-camera post processing effects.

There are some of these JPEG-only modes I feel comfortable with. Panoramas, as an example, don’t provide a raw file and you can’t bracket exposures. You have to trust the camera despite the huge range of tones and light a wide panorama can cover. If you choose your start position well (including the brightest highlight area of importance) exposure is very reliable, and at low ISO with Fine quality, the JPEG is of a professional standard.

Standard JPEG (click images for 1000 pixel wide version)

Three-shot HDR using 3EV spread

Three-shot HDR also works well, especially at low ISO settings of 50 or 100 and in Extra Fine JPEG. The 24 megapixel file gives plenty of scope for reducing to a smaller final result. There is also a special HDR Painting mode, which processes the file with a masking effect to create what is currently a popular ‘look’. Unlike the standard range of HDR settings, this is far from being a straight image and the lack of a raw file or normal JPEG to back it up means it’s only for fun.

Over the top with HDR Painting style, High strength – it actually works best on dull, wet days with grungy subjects!

More ‘only for fun’ stuff includes soft focus, selective colour against mono (called ‘Partial Color’), toy camera, miniature effect, two monochrome looks including one which uses three exposures, ‘pop color’, posterization, retro photo, soft high key. All of these are irreversible real time post processing. You have no normal backup when shooting.

The post-processing method offered by Nikon and others, where you can apply similar effects to raw or JPEG files already stored on your memory card and create a new version, is preferable. For standard HDR shots on Sony’s current models, a normal JPEG is saved along with the three-shot HDR and that’s good. For any of the Picture Effect post-processes, even multishot, no standard result is saved – all you get is the processed file, after a wait of 10 seconds or considerably less.

Selective yellow on monochrome – but that’s the only shot I have. No raw, no standard JPEG…

You do get a pretty accurate preview of the result in the EVF. If the stop-down preview button is set to ‘Shot Preview’ mode instead of ‘Aperture Preview’, you also get a simulation of the effect of your shutter speed – so flowing water brief time exposures (up to 30 seconds) can be previewed to see exactly which shutter speed suits the water movement best. Along with exposure simulation, there should be no reason why your shot ever goes wrong.

The Auto ISO Multi-Shot mode, Multi-Frame Noise Reduction, captures six frames and creates one JPEG. The pixel alignment seems very accurate and shots at settings like ISO 3200 show an improvement in detail which would be hard to obtain even by good raw processing. It’s not so much the noise that is reduced, it’s the overall quality of the image which improves. Using the high 25,600 ISO setting which can only be accessed in this mode shows that it’s slightly inferior to a straight 16,000 ISO shot despite the six-frame synthesis.

For all these multi-shot modes, the 12fps function of the Alpha 77, SSS, and the quiet, mirrorless shutter action combine well. They are all usable without much effort or worry, hand-held. The one ‘tonal range’ adjustment which does operate in RAW+JPEG mode, though only the JPEG is changed, is the DRO or DRO+ setting which uses a single shot.

High speed shooting also benefits exposure, DRO and white balance bracketing. Early information and the use manual state that you can define the number of exposures for bracketing, and the range covered, with the Alpha 65. In fact it is limited to three shots. The Alpha 77 gives you a choice of 3 shots at +/-3EV, the same at 2EV, then 3 or 5 shots at 0.7, 0.5 or 0.3 EV intervals. It is missing the obvious 1 EV step choices and that will baffle many, especially HDR raw users who would like 5 shots at 1 EV intervals.

Flash

The Alpha 77 has a proper, threaded, high grade studio flash sync terminal as well as the usual Minolta i-type hot shoe. Like the Alpha 700 and 900 (and unlike the consumer level cameras, including the Alpha 580) it can have the HVL-F58AM or 43AM wireless control capable flash mounted on the camera to control group/channel wireless strobes with power ratio. It can also use HSS (burst flash with shutter speeds up to 1/8,000th and corresponding power attenuation). It can not officially use the HVL-F20AM as a wireless controller, but owners have found it works – with a slightly longer than normal delay in flash firing, according to Gary Friedman, who has compared it with the pop-up flash wireless control.

The flash sync Prontor-Compur coaxial connector (PC flash socket) is sealed behind a cover shared with the Remote Release socket. This cover was so tightly sealed it threateed to break a fingernail opening it the first time, a small screwdriver was needed.

The most important change for professional and enthusiast owners is the long-overdue addition of a menu item which prevents the EVF or LCD live view from showing actual exposure when Manual aperture and shutter are set. This item is under Live View Display, and is called ‘Setting Effect’ – off or on. While this nomenclature is not exactly transparent, it describes the function well as all picture styles and creative effects normally shown in the finder are also bypassed. The important thing for studio flash users is that you can set 1/125 at f/16 with modelling lights, and see a normal finder view not a black hole. You still must remember to set white balance to Flash or Daylight, otherwise the camera will set it from the modelling light K.

It is best to use one of the three Memory registers (accessible through Menu screen after turning the Mode dial to MR, Memory Recall or Register) to store a manual exposure, fixed WB, low ISO, Setting Effect OFF preset for studio work. Then you can return to any other setting and get your accurate exposure and ‘look’ preview back again.

The internal pop-up flash (GN12) has the usual range of first, second curtain, fill-in, off, auto options; TTL Pre-Flash, ADI, and also manual power control down to 1/16th which can be useful for triggering slave flashes if you don’t have a cable or a wireless trigger (and Minolta shoe adaptor). Because the body is weatherproofed, the flash shoe cover is a softer plastic type which seals tightly. Don’t lose this shoe cover or swap it for one of your others.

And the rest

By the time I’ve written this single review article, it will be one-third the length of the complete camera guide books we used to do for Hove twenty years ago. The Alpha 77 has so much more to discuss.

You will be concerned about high ISO quality, diffraction, resolution, having good enough lenses. I would question whether the new 16-50mm, used wide open, is a ‘good enough’ lens – let alone the 18-55mm SAM also being offered as a kit lens. Just don’t worry. Whatever your existing lenses are capable of doing, the 24 megapixel sensor will give you more of it. Let’s say your favourite lens is really only good up to 12 megapixels. It will be just as good if you use the 12 megapixel Medium size JPEG option on the Alpha 77, and if you do that, the 1.4X Smart Teleconverter function will also deliver a 12 megapixel drawn from the centre of the field only – so most likely just as good.

Rather too distant heron, shot using the 2X Smart Converter for JPEGs (this is actually a clip from a raw file processed in aCR to match). ISO 3200, 70-300mm SSM G lens. Click image for 1000 pixel version

Click image for 1000 pixel 100% size clip from ACR processed version (my density choice)

Click image for Capture One Pro 100% clip from raw (ditto)

Click image for in-camera processed (JPEG Fine, Low level of NR) 100% clip (camera’s density)

I am now shooting with auto ISO set to go from 100 to 3200 instead of 1600, I have started using Medium and Small JPEGs with DRO+ to ensure exposure correction for events type shots, I’ve tried all the lenses I have and the only thought is that I need to stick around f/8 to f/11 for safety. Balancing extra depth of field with a hint of diffraction loss. I’m using the manual focus ‘peaking’ function to check the accuracy of my AF (this shows a coloured line on correctly focused details, when the AF/MF button is pressed in). I am not so worried about low light, high ISO as I first thought. It’s actually as good as the 16 megapixel sensor when needed, and when it’s not, the extra resolution repays careful low ISO technique.

The new tilt, hinge, flip, swivel and cartwheel rear screen is just great for the few times I need to use it. The EVF may consume more power (470 images versus 530 per battery official rating) than the big rear screen but I no longer need to switch between the two for menu and function operations. Because of the new design, all positions found on other cameras from hanging-under to almost flat on top (R-1 style) are possible except facing forwards and positioned to the side. There are firmware or orientation sensor errors, as the imager can appear upside down in more than twisted position. The hinge design makes a vertical grip possible and also allows a wider range of tripods or quickmount plates.

The A77 has all the focus and AE hold and lock, slow sync, focus point shift, exposure over-ride and other key functions I need. It claims to be weatherproof, and having nearly broken that thumnbnail off opening the flash sync cover I do believe the seal is tight. The card slot door is not so reassuring and I see no trace of any proper sealing, not even a labyrinth design.

I am baffled by Sony’s indecision about ON/OFF switch design, the camera labelling is the reverse of the Alpha 55/33/35 or 580/560 etc, though the action is the same. The direction is the reverse of the NEX-5. But there is one consistency, to turn any camera on the movement is always from left to right – whether Alpha 100, 700, 900 and whether the switch is rotary or a slider. Maybe this is the rule they stick to.

You can not configure the directionality of the two control wheels, as you can with Nikon, and for some reason I have always tried to open or close the aperture by taking the wrong directione. That is because the wheel directions go against the old Minolta protocol that turning the aperture ring to the right opens up, turn to the left stops down.

Like the Alpha 700, the Alpha 77 has magnesium alloy body shell combined with other metal and plastic components. It has the proper strap-lug fixed into the mag alloy casting, like the 700 and 900. This lug and triangle-ring design, as opposed to the slot-type strap fixing of the lesser camera bodies, is always a clue that the structure is based on a good solid metal skeleton. The overall design and balance of the Alpha 77 are as good as any Alpha I’ve used. There are hints of the 700 and also some memories of the Dynax 7xi present in the sculpturing of the body. To those who say it looks a bit like a Canon, yes, it’s true that Canon design has caught up with 1990s Minolta style in the last couple of years…

Conclusion

From the initial press meeting with Sony, where cameras were prototypes and the images were not allowed to be shown, I decided that if I could work for a year with the Alpha 55 and have no problems then the Alpha 77 was a safe investment. The viewfinder is a pleasure to use, though EVFs differ from optical screens in one important respect, that the eye can not compensate for small errors in the dioptre setting. With an OVF like the Alpha 900, I can set the dioptre midway between what’s needed for my sight with and without glasses, and get along fine with either. That can not be done with the EVF and it demands a precise dioptre setting for each. I have found it more comfortable to use without specs, so they spend too much time perched on my head, hanging from my collar or stuffed into a pocket.

It will be another year before I know just how wise the decision to go with EVF SLT models has been. And maybe another ten thousand words.

– David KiIpatrick

Please read the comments for some notes on corrections, which I will continue to make.