Voigtländer FE 10mm f/5.6 and 15mm f/4.5 III

I got to try out the first new Voigtländer Sony FE mount lenses with electronic aperture setting and manual focus control with a quick overnight test during the UK Photography Show at the Birmingham National Exhibition Centre, on March 19th 2016. The pre-production 10mm f/5.6 Hyper-Wide-Heliar and 15mm f/4.5 Super-Wide-Heliar are two of a trio reaching the market in Spring 2016 – the third is a new version of the 12mm f/5.6 Ultra Wide-Heliar. We also tried the 10mm in Leica M mount; the test cameras were the Sony A7R II and Leica M 240.

First of all, no other Voigtländer lenses yet have the Sony E-mount with electronic connections, similar to the Zeiss Loxia models. Cosina, the manufacturer of Voigtländer lenses, also makes some Zeiss lenses and the operation of these designs is probably identical to Loxia 21mm, 35mm and 50mm models. The electronics could allow in-body control of the lens aperture but for these lenses, the aperture is mechanically set on the lens itself with a 1/3rd stop clicked ring that can be de-clicked by pushing back, turning through 180° and putting an alternative index mark in place. The focus distance set is transmitted to the camera, along with the focal length. This allows a digitalogue display in the finder, a marker moving on a bar from close to infinity.

For the E-mount, the close focus of the 10mm and 15mm is impressive and identical at 30cm. This contrasts with the M-mount minimum focus of just 50cm. The mechanical focus is very smooth indeed and the whole metal-bodied barrel and mount feels solid and precise. Depth of field markings are conventional (that is, based on pre-digital circles of confusion, or a typical A4 print rather than a 100% view on a 27 inch monitor screen). The optical design for the Leica M mount is clearly identical but the mount is very different with no electronics, and indeed no way of telling the Leica body the focal length or aperture in use. The EXIF data from Sony E-mount files is precise, with Leica it depends on the user manually entering the focal length, and a clever algorithm that uses the camera metering to work out the f-stop being used.

Here are 10mm Hyper-Wide-Heliars in E-mount and M-mount.

The lenses have fixed petal type lens hoods and come with well-fitting front caps. The use of filter systems will depend on adaptors like those already found for the 15mm MkIII Leica M, but probably custom designed for the 10mm.

Here, as a final product shot, is the original 1990s 12mm f/5.6 Ultra-Wide-Heliar Leica screw mount, with its detachable hood removed, next to the new 10mm. The new 12mm is similar in size to the 10mm, reflecting an optical design intended to be more compatible with digital sensors with improved vignetting control and freedom from colour shifts. It’s fair to say, though, that with the Sony A7R II I have been using the old 12mm with very good results. I can also tell you the new lenses are much sharper especially towards the corners.

It’s this sharpness which comes as a really welcome surprise with the 15mm f/4.5 design. It can be used wide open with confidence. Because the lenses have mechanical apertures, they don’t open up for focusing like purely electronic E-mount types – you focus at the working aperture, or for extra accuracy open the lens up, focus, then close down. When you touch the focus ring and move it, the magnified focusing of the Sony body is automatically activated, returning to a full view when you take first pressure on the shutter release. In practice this is a very fast and accurate manual focus method needing no button presses on the camera body.

The geometric distortion of the lenses is minimal – they are almost perfectly orthographic but far from isometric! Objects near the ends and corners of the image can appear extremely distorted simply because they are projected with such rigorously rectilinear drawing. This is not really distortion, but it certainly looks like it when a face or figure ends up placed at an extreme. The 15mm must be used with care, and the 10mm needs an advanced understanding of weirdness.

These lenses convey a built-in profile to the Sony bodies, and also to Adobe Lightroom or Camera Raw for processing (or so the dialog reports). What you see through the electronic viewfinder, and on opening a raw file, may not represent the optical truth. Studying the 10mm I found it hard to understand how any light reaches the corner of the sensor at all. I can’t measure the true fall off but I would guess it’s in the order of five or six stops. With the profile applied in-camera or by the raw converter, it’s moderated especially when stopped down a bit. This looks natural. Correct the vignetting fully, and some of the natural appeal of the image is lost.

We must wait to review what may be primary choice for many users, the 12mm.

The 10mm Hyper-Wide-Heliar f/5.6

This lens displays an exceptionally straight geometry, even when used on the Leica M 240 body which has no added firmware correction function. Whatever profile is being passed to the Sony bodies probably only concerns vignetting (our Leica test indicated it may not really need a lens profile). It has 13 elements in 10 groups and covers the widest angle ever achieved with a true wide-angle on the 35mm format, 130°.

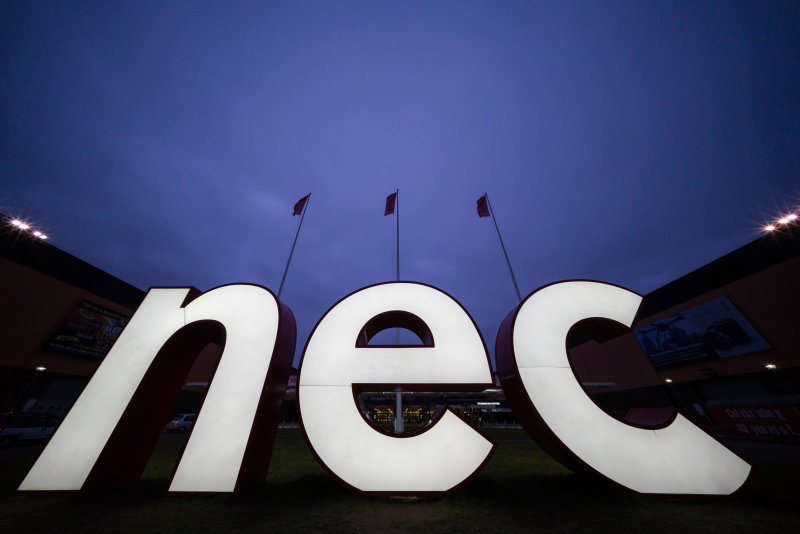

Of course, I took a few tests inside the NEC but the first subject which really lent itself to the extreme angle was the giant illuminated sign. I was about a metre away from this, but a standing adult is about half the height of the letters. All the pictures used in this article can be clicked-through and will take you to the pBase Gallery which allows access to the ‘Original’ A7RII (level 10 JPEGs, full size) along with all the essential metadata. Please note these pictures are all copyright and if you wish to share them, please link to the pBase Gallery. You may download and examine them for your own research but they may not be reproduced.

Outside the exhibition centre there’s an open land drain (Pendigo Lake) which stops the entire place from flooding. It’s about seven feet deep and fed by drains from below all the exhibition halls. With the 10mm fitted, I found a suitable supporting post. You’ll see that the beach gravel shows some softening and elongation towards the corners, almost inevitable regardless of the sensor cover glass specifications sometimes blamed for this. The lens geometry forces the elongation. This shot at f/8 has no added correction at all for vignetting.

But with a lens like this, simple extreme wide views can be disappointing or pointless. You need to exploit its potential to do what other lenses can not do. The Sony A7R II can also go where other cameras might not – such as nested into the gravel, using the rear screen folded out for viewing the composition.

This is stopped down to f/22, and in fairness the diffraction softening means nothing is really as sharp as it can be. The diaphragm stars from the lights are neat. Depth of field doesn’t get much deeper than this.

This picture is from the next morning, walking back past the lake. ‘Not often you get to photograph Father Christmas fishing’, my friend here joked. He told me the history of the ‘lake’. Seven friends had gathered, for a fishing competition – pick their spot, set up, three hours to fish, winner with the biggest catch by weight. I’d been using a tripod so Steady Shot was turned off, and this hand-held shot at 1/6th was just OK. I found that because of the magnified scale of detail towards the outer field, if you do get shake it can be almost invisible in the centre but really blur the corners. I’m still trying to work out exactly why sensor based stabilisation manages to handle this change of scale caused by lens projection, but it does. Shots with SS on were generally perfect, those without could be surprisingly poor considering the very short focal length. I’ve processed this picture a little to suit the subject, but it shows the potential of the 10mm for environmental portraiture and editorial work. Because a shift of just inches in the lens position changes the shot so much with the 10mm, a tripod would have been impossibe here (I was leaning forward almost vertically above his foot for this).

Here’s a funky use of the 10mm extreme angle and scalar distortion. It’s a quick grabbed shot on leaving the exhibition hall, and it’s not even vaguely sharp, except rather oddly in the view through the coach windows. The LED lighting has strobed some detail at the left hand side.

I liked the effect with the bus so much I tried a few trucks through the car window in the morning. However, they lacked shape and form. This passing car and trailer was about the best. The progressive shutter captures a very strange effect from the wheels.

Here’s a more conventional use of the 10mm. The weather was pretty dull and actually, night scenes were better. Stopping right down, again, takes the edge off sharpness. The 10mm seems about at its best around f/8 or f/11 (which is exactly where I use the old 12mm at the moment).

Before moving on to the 15mm, a change of location. Next to the ‘lake’ there’s a new Resorts World hotel, casino and outlet mall complex with restaurants. Brightly lit at night, it was a far better subject for these wide lenses than anything else! Even in the daylight, it was interesting.

You’ll also find a vertical version of this in the pBase gallery. It’s hand held, and the detail throughout really says everything you need to know about the 10mm and its practical uses. Although I believe the 15mm is substantially better optically – simply not as ‘stretched’ – I placed my order for a 10mm after doing this test. It is, after all, about the same price as Sony’s supremely boring but widely praised CZ 55mm f/1.8 – and you’re getting something with a unique commercial and creative edge instead of exactly the same old standard lens we’ve had around for ninety years, slightly improved…

The 15mm Super-Wide-Heliar f/4.5

With only 11 elements in 9 groups, this 110° lens is version III of a popular favourite. Optically identical to the M mount version, the big attraction is not just the lens, but the E-mount functionality. However, having used various 15mms before version III, I have to say this lens is just outstanding optically. It resolved such fine detail that on the interior view at night of the Resorts World mall, moiré patterns are thrown up by the pattern of pegboard type holes in the architectural ceiling surface. Please note that’s not vignetting at the top, below, it’s the lighting in the mall.

Even if you don’t bother to click through and examine the full sized images for the other shots, please do take a look at this. It’s also handheld with SS, and not at the very slowest ISO. The resolution at f/8 is extreme and other shots taken, including those at f/4.5 maximum aperture, show the same quality. I’ve been testing lenses for over 40 years now and this is simply one of the best lenses I have used. This particular interior is almost like a 3D test target for lenses, too!

The 15mm causes me a problem. I already own a Sony CZ 16-35mm f/4 and it simply isn’t this sharp. It can’t do the same thing on a 42 megapixel sensor, it is acceptable and all very good, but not on this level. The 15mm is better than the 10mm and in many ways a more generally useful focal length. But… I’ve got my 16mm covered. 10mm is a better partner. If I dd not have my 16-35mm, I’d team up the Voigtländer 15mm with a 24-70mm. Only even the new 24-70mm Sony f/2.8 probably won’t match this (I have taken a few shots on a pre-production sample, but remember, this Voigtländer is also pre-production).

The 15mm is a great angle for shots like this and it resists flare well. This is not a tripod shot, it used the fishing platform at some risk of an expensive camera and lens taking a dive.

Here’s a hand-held, stabilised, very high ISO shot stopped down enough to keep the topiary fairly sharp. It’s much easier to get the horizon level with the display function available in the Sony A7R II and the brightness of the EVF for night shots. Otherwise, this would be much harder. I found it almost easy to take pictures like this casually using the 15mm (it’s harder with the 10mm which needs that little bit more care in levelling up).

The 10mm on Leica

Just to prove that the straight-line geometry and reasonable vignetting are not entirely down to any kind of electronic profile, a couple of Leica 240 shots start here with one using no adjustments in raw conversion to correct illumination or geometry.

Here’s a slightly more creative use of the lens. Getting the camera in position was not easy and the A7R II would have been quicker to set up, but we wanted to check out the Leica version too.

Conclusion

If you have not purchased any wide-angles shorter than 20mm, it’s worth buying both the 15mm and the 10mm – or maybe just the 12mm on its own. The prices in the UK should be around £839 including VAT for the E-mount 10mm and £724 inc VAT for the 15mm – or less. At The Photography Show, these lenses were being ordered in some quantity especially on the professional days. A surprising number of mainstream professionals now use Sony A7R II and it seemed that almost all my pro magazine readers who came for a chat at the Master Photographers Association stand either had Sony or Fujifilm X. Those handling commercial assignments generally had the A7R II and most were using their Sony kit alongside Nikon or Canon. You can get pretty good (if huge) 15mm lenses for these DSLRs but you simply can’t get a 10mm. The closest is Canon’s 11-24mm EF zoom; at 11mm this does not even begin to approach the image quality of the Hyper-Wide-Heliar. You could also buy an A7R II with this lens for less than this zoom alone (definitely so at the show prices where £700 was slashed off the A7R II body).

For those who own 16-35mm or similar lenses, the 10mm is a logical buy. It’s especially useful with the A7R II rather than the A7 II or A7S models, because the 42 megapixel sensor allows sensible cropping away of geometric extremes. One photographer I talked placed an order just to dispense with his bulky Canon 17mm tilt shift and DSLR – a crop from the 10mm angle of view is all he reckons he’ll need in future.

Our thanks for Hardy Haase of UK distributors Flaghead for the overnight loan of the lenses, and thanks to the NEC and Resorts World environmental landscaping completed this year for creating some half-decent subject matter. Flaghead is also the owner of Robert White, the famous UK professional dealership in Poole, Dorset, whose founder is no longer with us. They took over the premises and shop before Robert’s death, and continue his name and reputation. This is their own direct outlet for the Voigtländer lenses

– report and all example photographs by David Kilpatrick, publisher and editor of f2 Cameracraft and Master Photography magazines. Product photographs by Richard Kilpatrick. To subscribe to our premium quality bi-monthly magazines, visit www.iconpublications.com

See: Flaghead – www.flaghead.co.uk; Robert White – www.robertwhite.co.uk; US distributor, CameraQuest – Cameraquest.com; B&H for US orders, 10mm lens E-mount link, B&H product listing.