The Sony Zeiss 24mm f/2 SSM Distagon ZA T* is probably the best, or equal to the best, in its class. It may perhaps be the best ever 84° angle fast lens ever made for the general SLR system market, and I would happy to pitch it against any of the current equivalent offerings for medium format digital.

The initial journey with the 24mm f/2 was not one of intensive companionship – I am long past the stage of getting hold of a wonderful lens and then shoehorning all my photographs into that lens’s view just because I love the glass. I’ve been through that phase. I remember when I was 18 and my then fiancée (Shirley – still here!) bought me a brand new 35mm f/3.5 SMC Takumar, my first ever multicoated lens as well as my first new boxed product. I shot almost everything with that lens for a month…

A full-frame Alpha 900 study at full f/2 aperture. Check the sharpness in the central – very limited – sharp focus zone by clicking the image for a full size version.

My review of the 24mm appears in the British Journal of Photography for January 2012 but was written in November, and at the end I comment that I do not think I would buy one. Well, between writing that and publication – after returning the test lens loaned to me by Paul Genge of Sony UK – I placed my order. I sold a set of lenses including a 28mm f/2 Minolta RS and a 17-35mm Konica Minolta D to pay for it.

Check current availability and price at B&H Photo Video (opens in a new window will not lose this page).

Why?

It was partly medium format which persuaded me. I’ve been experimenting with MF digital, first using a Hasselblad with a Phase One P20 and then shifting to a Mamiya 645 AFII with a 22 megapixel ZD 37 x 49mm back. Once you put the Zeiss on the Alpha 900, the image quality jumps to match the level of a similar MF pixel count. And without spending into the tens of thousands you can’t match the angle of view at a higher pixel count.

These two cameras both shoot 22 megapixels over a 16 x 12″ print shape (the Alpha 900 being cropped) and both were current in 2008 – though the Mamiya ZD model was shortly to disappear. And the two lenses have similar coverage.

I looked at the corners of my MF shots on a 35mm lens (nearly identical angle of view) – to be clean, they demanded f/11. And then I looked at the corners on the Zeiss, which are even cleaner by f/4. Finally, I considered what Sony may have in store – 36 megapixels on full frame. Everything I’ve seen from the 24mm – including its performance on the A77 and A55 – indicates it will not run out of resolution even if full frame goes well over 50 megapixels.

Then I had the job of looking back over the Alpha 900, Alpha 55 and Alpha 77 pictures taken with the 24mm, and preparing some comparison shots. This was when I realised that my normal line-up of zooms, no matter how good, never got the same from any camera – APS-C or full frame – as this CZ prime. It may be bulky, take large filters, and cost nearly £1,000 but no other solution on any format from NEX through A77 to MF offered the same as the 24mm on Alpha 900. You will, however, be surprised later on to see just how well the tiny NEX 16mm f/2.8 does in comparison when both lenses are stopped down to f/8.

The 35mm 2:3 format shape offers a bit of vertical composition ‘rise or fall’ potential compared to to 3:4 shape of my Mamiya with 35mm wide–angle. Beyond this, the 24mm offers both CD and PD focus with different adaptors on the NEX system, and smooth near-silent AF during video on the Alpha 65/77 and future models. It’s both future-proof and a future classic.

Photojournalism or architecture

Because the 24mm has a fast f/2 maximum aperture, it’s seen as a choice for news, documentary, reportage, sports, and close quarters party or family shooting. Though a little vulnerable because of its size, it does this job well. Unlike tele lenses, any mark on the front glass of a wide-angle like this will show in pictures when the aperture is stopped down. Special care should always be taken of retrofocus and fisheye lenses with vulnerable front elements, my own lens will get a Sigma EX DG 72mm UV filter. Why Sigma? I ran a series of ad hoc tests on filters and these turned out to be just as good as Hoya Pro 1 Digital at half the price, and with better multicoating.

At f/2, struggling with light for a hand-held shot with 1/40th at ISO 1600 on the Alpha 55, the 24mm showed surprisingly clean imaging from the boat to the lights on the cliff top.

Here’s a shot taken at f/2.5, 2/3rds of a stop down from wide open – a sensible aperture to give that hint of extra depth of field and improved optical performance. Click the image to view a full size A55 image on pBase.

When fitted to my A55 or A77, the 35mm-equivalent field of view is also a good general lens for photojournalism (what you get is more or less a Fuji X100 equivalent, but hardly pocketable). The performance over the APS-C field of view is so good that working at full aperture carries little penalty at all except restricted depth of field. The geometry and field flatness over the restricted field mean you could use the lens for artwork copying and get a better result than the 50mm f/1.4 of 30mm f/2.8 SAM macro will produce.

Over full frame, this technical excellence makes the lens attractive to the commercial, industrial and architectural photographer. Whenever you need to apply a strong software correction, focal length figures are thrown out of the window. For example, once the on-board lens correction in the A77 is applied to the 16-50mm f/2.8 SSM lens at 16mm the true minimum focal length equivalent becomes close to 17mm not 16mm.

Hasselblad’s 28mm superwide for its HD series cameras has strong barrel distortion, relying on in-camera and Phocus raw software converter functions to remove it. So while the lens claims to be a 17mm equivalent, that is only true over absolute full-frame 645. On their digital sensors, it’s only equal to a 21mm and the correction means the true crop is more like a 23mm.

A second effect of applying any in-camera or post-process distortion correction is loss of true image pixels. Either you crop the frame after sampling down, or the image is interpolated upwards to fill the frame. Both solutions are far from satisfactory because unlike a fixed interpolation, the value ranges from 0 to whatever maximum is involved (typically between 3% and 7%) and all of this is never a clean ratio.

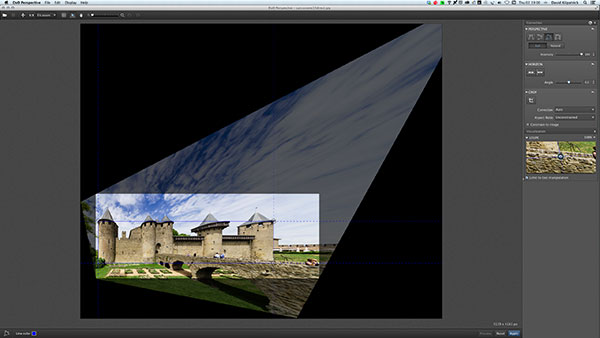

Above: a sea horizon (the top of the crop is the top of the frame, and it is full width). Top, CZ 16-80mm at 16mm 0n Alpha 77, uncorrected, showing complex wave-form distortion as well as vignetting despite stopping down to f/11. Centre: CZ 24mm on Alpha 900, uncorrected, at f/13. Bottom: 24mm after applying a 2% barrel distortion correction. Click image to view a larger version.

Here the 24mm CZ shines. It really uses all the 24 megapixels of the A900 or indeed the A77, because geometric correction rarely needs to be applied. It has a true 24mm focal length which does not need to be quietly changed to 25mm or 26mm by applying a lens profile. If a 35mm retrofocus AF lens was made for MF digital to this standard, even without the f/2 aperture, it would be hailed as a world-beater. The most that’s needed is a correction of 2% (+, removing barrel distortion) in Adobe Camera Raw and this restores something like a sea horizon near the top of a landscape format frame to a perfect straight line.

No correction is applied here to this full frame 24mm Alpha 900 image – a central horizon, and straight lines which are not parallel to the frame edge, make the 2% distortion (similar to many standard 50mm lenses) no issue at all.

For many subjects, depending on the distance and a ‘rigour’ of the shot (the sea horizon is the most demanding example) no correction at all will be needed. This applies to most interiors, and always to scenes like mountain views or forest landscapes where there is no perfectly flat horizon.

The Alpha 900 is so close to MF digital quality I should really forget the attractions of MF systems. Nearly everything I see from them which impresses me is down to using prime lenses of first quality like the Zeiss and Mamiya 80mm f/2.8 standards and working in a methodical way often using a tripod, minimum ISO, mirror-up operation. Applying the same parameters to Alpha full frame lifts the end result to match – and the CZ 24mm f/2 is a key to unlock that quality.

At f/14, the 24mm is not losing detail sharpness on the Alpha 900 as long as the correct raw processing parameters are applied. To secure this depth of field, f/14 was needed – a medium format camera would require f/27. Holding the camera, viewing and composing this shot were all aided by the ergonomics, weight and viewfinder quality of the Alpha 900. Click image for a full size version on pBase.

This is a dual-purpose or multi-purpose lens. Where the 16mm focal length of the NEX SEL 16mm f/2.8, the Alpha SAL 16-50mm f/2.8, the CZ 16-80mm or SAL 16-105mm all cover the same nominal angle not one of these has the same neutral geometry, even illumination and good corner to corner sharpness at wider apertures. Corrected by software, they don’t have the same true angle and the outer field can become noisy because of extra sensor-mapping gain applied to reduce vignetting.

The size and SEL comparison!

But I would like to show you something surprising. I am a great fan of the 16mm NEX f/2.8 pancake, which is one of the few such lenses made to have a positive (pincushion) simple distortion pattern and a cup not cap shaped field of focus. It is a revolutionary inverted telephoto design of great simplicity, with only 5 elements, enabling the lens to be 16mm focal length yet have a rear node position over 20mm from the sensor – thus avoiding all kinds of vignetting and colour shift problems.

People who don’t understand how to use a focus plane where the corners are focused FURTHER than the centre – the exact opposite of the CZ 24mm f/2 where the corners are focused CLOSER than the centre – do tests like landscapes wide open and wonder why the grass either side of their feet dissolves into blur. Actually all the little 16mm needs is modest stopping down, as would be applied by any professional using a Super Angulon for that matter, to f/8.

First of all, have a look at some lens sizes. I like this shot, as it shows just how big CZ had to make the 24mm to get what they did. It dwarfs the SEL 16mm for NEX and the classic Minolta 28mm f/2 RS:

I’d like you to see the exact comparison between Alpha 900 with 24mm CZ and NEX-5 with SEL 16mm.

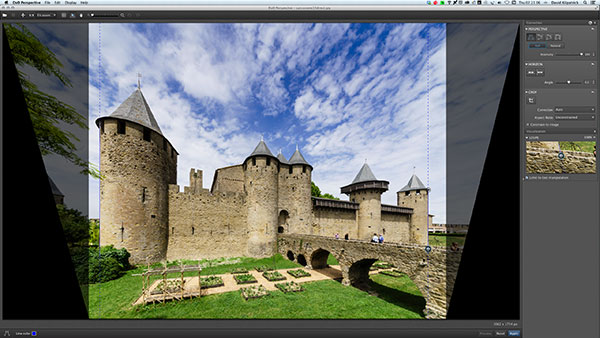

This is the A900 and 24mm, entirely uncorrected and uncropped – the building on the right actually does not have a straight wall, don’t be fooled into thinking there’s a sudden burst of barrel distortion! Aperture f/8.

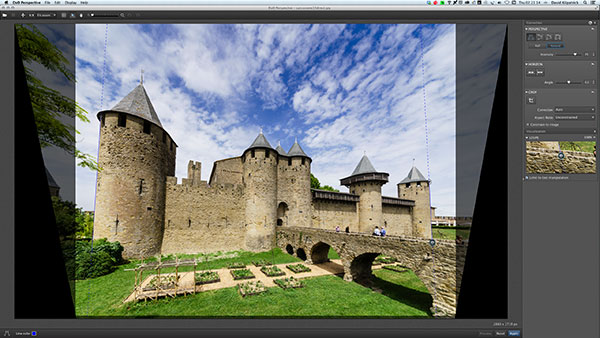

This the NEX with 16mm, corrected in ACR; I’ve tried to keep the camera positions very close but this was real-time shooting and with viewfinder versus screen composition, not so easy. You can see that the 16mm has slightly less true angle of view when corrected but don’t judge from the foreground flower tub, just check the horizontal angle. This is also at f/8.

You can click each image and view a full size JPEG. I have made both of them 24 megapixels, exporting from the NEX to the same size file as the Alpha 900. That may be unfair but you can judge. My opinion is that both the NEX 14 megapixel sensor and the SEL 16mm are underestimated by far too many owners; as far as ISO noise handling goes, the 16mm f/2.8 on NEX is actually as ‘fast’ as the 24mm f/2 on Alpha 900 but that comparison may change with future full frame bodies. As for depth of field, the f/8 shot on APS-C would need to be at f/13 on full frame to match, but in practice both are well covered.

Using the NEX 16mm in different conditions would produce a different result – wide open in a room interior, the corners would be likely to look very blurred. My scene above conforms to the cup-shape focus plane of the NEX lens, and works against the cap-shape focus plane of the CZ 24mm.

Remember as a general rule: barrel distortion = corners focused close than centre. Pincushion distortion = corners focused further away than centre. Moustache or wave form = a doughnut normally of closer focus between centre and corners, but when a full frame lens with this type of distortion (like the 16-35mm CZf/2.8 – or a more extreme example, Canon’s 24-105mm f/4 L) is used on APS-C, you get this doughnut at the corners and more or less have straight barrel distortion not waveform. No distortion at a given distance usually means a flat focus field, the quality which Carl Zeiss highlighted when naming the Planar lens.

Alternatives to the 24mm

The best way to get the 84° coverage with similar near-perfect rendering is to go for the mid-range of a high end zoom. As it happens, Sigma’s 8-16mm is better at 16mm than any of the above-mentioned APS-C options and you can also get a pretty good 16mm from their 10-20mm options and Tamron’s 10-24mm. Tokina’s 11-16mm f/2.8 is weakest at 16mm, best at 11mm. The older Sony 11-18mm is not wonderful at the longer end.

On full format, 24mm at the bottom end of the 24-70mm CZ is no match, it has more distortion and softer corners; 24mm in the middle of the 16-35mm CZ f/2.8’s range is better but with strong complex distortion, more even than the Konica Minolta 17-35mm f/2.8-4 D lens (which manages f/3.2 wide open at 24mm). You might think Sigma’s 12-24mm full frame zoom could be good at 24mm, and perhaps version II HSM when it finally become available for Alpha will prove to be. The original, which I still use mainly for its superb 12mm results, places its worst extreme of field flatness deviation at the image edge when set to 24mm.

I have used Canon’s 24mm f/1.4 USMII and this is faster, larger and more expensive than the Sony CZ lens in almost perfect proportion. Like the CZ f/2 it is a nearly perfect lens, with a hint more barrel distortion and slightly soft extreme corners on full frame wide open. The same goes for the Nikon 24mm f/1.4. I’ve also used Canon’s 24mm TSE tilt-shift and this lens betters the CZ for technical and architectural uses, as it should – so does their 17mm f/4 TSE, which has no match in any format. But such lenses can’t also be used for everyday autofocus image grabbing whether professional or family.

Last question, then. If such a perfect lens can be made at f/2, surely all the affordable 24mm f/2.8 designs could be just as good? We wish! Wouldn’t it be great if the classic Minolta 24mm f/2.8 AF which Sony never transferred to the new Alpha range proved to have the same optical excellence as the CZ? It does not. Nor do the Canon 24mm f/2.8, or the Nikon, or anything made by Pentax or Olympus, or even Leica.

The 24mm f/2 used at f/2.8 on the Alpha 55. Try this with a classic Minolta 24mm f/2.8 and even on APS-C you won’t get the same corner to corner even illumination. Here the focus is on the distance, not the tourists – they are also showing a surprising amount of movement at 1/40th. Click the image for a full size view.

This 24mm is the most recent AF 24mm prime lens to have been designed for full format. Zeiss have designed a slightly more complex manual focus 25mm f/2 Distagon for Cosina partnered manufacture, available for Canon and Nikon, since Sony showed the 24mm at photokina 2010. But Sony’s full-frame DSLR rivals, Canon and Nikon, have not gone for this sub-£1,000 RRP ‘moderately fast’ 24mm niche.

If there’s one competitor, it is Sigma’s excellent 24mm f/1.8 EX DG, which uses a larger 77mm front diameter glass unit to reduce vignetting to the absolute minimum. Distortion is higher, and the lens at present has no HSM version. This makes it less future-proof for Alpha system owners, and also less compatible with NEX and with video shooting in general.

Features of the 24mm

Because it’s a fixed focal length, the 24mm is a very plain lens – it has only two controls and one moving ring. There is an AF/MF switch, though unlike SAM lenses this lens can always be controlled from the body. With SAM type lenses (built in non-supersonic focus motor) it is essential to use only the lens switch, and never to use the body switch instead while leaving the lens set to AF. This is because any attempt to focus manually may damage the gears and motor unless the switch on the lens is specifically disengaged.

Manual focus or held focus can be set or toggled using the single on-lens button. New Alpha models like the 77 allow a wider range of functions to be assigned to the lens button, which is described in the menus as a Focus Hold button. Direct Manual Focus is also supported on bodies which offer DMF, meaning that once focus is confirmed and locked by your pressure on the shutter button, you can fine-tune focus by eye before firing.

The manual focus action is very smooth and well balanced, not too light and not too short in throw (which can be an issue with shorter focal lengths. The focus scale is minimal, behind a traditional Minolta-style clear window, with a depth of field indicator to the minimum f/22 aperture. Really, such markings mean little today as we expect so much from higher resolution sensors. It is time that Sony, and others, built parameter-governed DoF calculation into firmware.

Here, f/5.6 was judged to be fine for the degree of differential focus wanted – at ISO 400, by tungsten kitchen spotlights and window light mixed, on the Alpha 77 hand-held with SteadyShot and manual ‘peaking’ focus.

The CZ design is clearly corrected for medium distance work but retains its performance for close-ups. Unlike Sigma’s design which achieves 1:2.7 image scale, or the new manual Zeiss 25mm which focuses down to 18cm and 1:4, the Alpha lens focuses to 19cm (actually, I make it 18cm as the scale goes beyond the 19cm marking) and manages a 1:3.4 image. Don’t be fooled by distances! The front element of the CZ is already 12.2cm from the sensor plane, and the lens hood takes another 3cm or so. The actual clearance when shooting at close range is minimal. For comparison, the SEL 16mm f/2.8 for NEX will only focus down to 24cm, and the front of this lens is only 40mm from the sensor, leaving a clear 20cm between camera and subject. The Nikon and Canon f/1.4 designs are limited to 25cm and are, quite simply, nothing like as useful for close-ups as the CZ.

You might think that the 16-50mm f/2.8 or the 16-80mm CZ could match the combination of wide angle and close focus found on the 24mm – but not so. To get similar close-ups even at a 24mm setting is not possible – an extra 6 or 7cm in minimum focus distance, when you are talking an 83-84° angle of view, makes a big difference.

Moving in to minimum focus, the bottom wing of the lens hood was only 1cm away from the subject – under 19cm from bread roll to sensor, but only 6.8cm from bread roll to front element. At f/3.2, a hand-held 1/40th was needed (the closer you get, the less you can rely on SS to handle speeds like 1/15th). Focus peaking again enabled the manual focus point to be precisely judged. Great bokeh too.

With a non-rotating front thread, 72mm is one of the classic Minolta sizes. It is necessary to use slimline filters, as with the 20mm f/2.8. It’s interesting to compare the revived older lens with the newer one. The 20mm has only five mount contacts, being non-D specification where the 24mm has eight and reports much more accurate focus data. The 20mm has no lens button, uses screw drive focus, and has a close limit of 25cm at which it has a 1:7.7 image scale. There is also a considerable difference in the build and feel of the CZ; I have no doubt it contains some plastic, but it feels like a good solid piece of engineering and is stated by Sony to have a metal lens barrel. Not metal-skinned plastic, like NEX lenses.

As for coatings, Minolta’s legacy was a use of multiple layer (super achromatic) coatings to rebalance both the contrast and the colour transmission of the entire AF lens range (except designs made by third parties, like the 100-400mm APO). This advantage over other makes was never capitalised on, and made some Minolta designs seem lower in contrast than competitor’s equivalents. No-one ever complained about the colour though! Zeiss’s path from 1975 onwards was to use multicoatings a different way, maximising contrast and light transmission but permitting each lens design to have its own colour transmission quality and variation in contrast. Contax RTS lenses were always praised for their resistance to flare and their extreme macrocontrast.

Since the advent of digital, both overall contrast and colour transmission have become less critical – no need for packs of filters to balance lenses for repro purposes, no need to test Kodachrome with a clip-test to set this up. Just post process or shoot a WB card to taste. Also, Sony Alpha lenses are made in many places – the old Minolta unit, the new CZ-Sony collaboration, co-developed with Tamron and apparently also with Sigma, built by Shanghai Optical or some other owned and partnership facilities in China, made in Thailand but not apparently any more in Malaysia…

While distortion associated with viewpoint and perspective perception is always a companion to shorter focal lengths, over the field of the Alpha 77 (equal to a 35mm lens view or so, in full-frame terms) shapes and solids look natural. At f/4, and ISO 1250, I’ve chosen to downsize this 77 file to 3600 x 2400 pixels (click the image to open). This still allows you to see how clean the light sources in-shot are, with absence of colour fringes. Depending on conditions 1 pixel CA cancelling may be needed with the 24mm.

So, we have here a lens with a Zeiss design and a T* coating which is entirely unlike any Minolta legacy design and will surprise those used to the way ex-Minolta lenses perform. It is fairly immune to flare, not entirely so when confronted with bright sources just outside the image margin, but without the strings of coloured patches associated with 24mms and light sources in the shot. It focuses silently and at a speed which means you may not notice it.

The lens itself weighs 555g, and at 76mm length and 78mm diameter it’s smaller than the 16-50mm f/2.8 SSM which weighs 22g more. I’m not a big fan of lenses you can not clasp in one hand while also operating the lens release mount of a camera; optics this size and weight are about the safe limit. You can not compared the lens-juggling friendliness of the 28mm f/2, for example, with either the 24mm or 16-50mm and even the 16-80mm zoom is much easier to handle in the field. It’s best to remove or fit the hood before changing the lens, don’t leave it in storage position.

The hood reverses over the lens neatly. The whole item, when in this configuration, is a bit large to handle for safe and secure lens changing.

The finish is lustrous, with rubber rib grips that collect dust and dander readily. The supplied lens hood is surprisingly flexible plastic, with a slight spatter finish to the exterior and a kind of semi-flock paint on the inside. It is efficient, but a poor fit with a not very firm bayonet locking action. It’s easy to get the alignment wrong and it’s not as firm or solid as most other Sony hoods. The rear lens cap is still the frustrating one-orientation only design inherited from Minolta, which leaves even those with a quarter of a century of lenscap-fitting experience fumbling for the correct position.

There is of course a Zeiss front lens cap and you get a free blue badge on the lens itself!

Format, pixel count and cropping

For many years when using film I found wide-angle zooms were not essential, standard zooms were useful, and tele zooms were vital. Generally, with any wide-angle you can zoom with your feet or by doing little more than leaning forward or back a bit. Either that or you simply need the widest lens you can get. Whenever I fit my Sigma 8-16mm or 12-24mm on their respective formats it’s the 8mm or 12mm end which is needed. I only end up zooming in if for some reason I decide to leave the lens on, and move to a different situation without time to switch lenses.

With film, you could crop and enlarge. Small pixel count DSLRs made that difficult or impossible – when you are trying to make 6 megapixels do a full page magazine image, cropping is not an option. Zooming in to fill the frame every time became vital from 2000 to 2008 when the first full frame 24 megapixel models arrived.

I think that 24 megapixels has finally made cropping an alternative to zooming. You may need 9 or maybe 12 megapixels, or if you are shooting entirely for the web you may need no more than 2 megapixels. Fixed focal lengths of exceptional quality, sharp all over the frame in the plane of focus, start to be useful. It has never been a good option to crop wide-angle zoom shots asymmetrically, using just one corner. With a lens like the 24mm you can crop any composition out of the high resolution frame and it will not look so different from an on-axis shot with a narrow angle lens.

Lens resolution really does count, as I have found. For three years I used the Alpha 900 with a range of lenses, including the 24-85mm Minolta RS I keep for convenience. When working with medium format lenses on adaptors, I could see that zooms while ‘sharp enough’ usually came nowhere near realising the potential of the 900. Then, using the 24mm, I saw the same pixel-level sharpness pop out. After a month using the 24mm (kindly loaned by Paul Genge) my ordered Alpha 77 finally arrived. I had already seen how the 24mm got the maximum from 16 megapixel APS-C, and this was followed by discovering its power to do the same at 24 megapixel APS-C.

A standard Sony leather-look lens posing pouch is supplied.

How far can this go? If Sony’s 24 megapixel APS-C sensor formed the basis for a full-framer, it would be a 60 megapixel monster and match all but the most expensive medium format image sizes. I believe the 24mm CZ could go there if Sony chose to.

And that, in the end, is why I changed my mind about owning one. The hour or two of useful daylight and howling gales outside have not allowed me to make much use of it yet – but this is a lens for the long term. And for tomorrow’s Alphas as well as today’s.

– David Kilpatrick

Footnote: added February 2016 – I’m now selling this lens, as I don’t think Sony is likely to produce an A99 model II with functions that will restore what I want to have (notably, GPS – they are most likely to drop this). I’m looking at a move to native FE-mount lenses and probably the 25mm f/2 CZ Batis, even though it’s weaker for close-ups, vignetting and distortion.

Here is a recent example of a full aperture shot on the A7RII with LA-EA3 adaptor –

http://www.pbase.com/davidkilpatrick/image/162677066