I guess it’s time to publish another field test review of the Alpha 7R despite rarely having used the camera in anger, or in any state other than anger. It arrived in late November and caught me at a time when I was not going anywhere or doing anything, nothing was happening and the weather was just plain ordinary. We didn’t have floods, or snow, or anything else like the rest of the country. It also came with a set of problems to be solved some of which turned out to frustrate any affordable solution.

I started writing this page in February 2014. It may give you some idea of my issues with the whole current Sony system that I’ve taken almost until May to publish it. Additions have been made on December 2nd 2014.

When you’ve got a wonderful new tool to work with, it doesn’t help to have no work to do which requires that tool. This really is the Swiss Army Knife camera, a strapline I used on the first issue of the new-look f2 Freelance Photographer magazine which I took back into ownership at the end of January. The A7R has the potential to fit in my pocket and replace every single other camera I own, to use all the lenses I have bought for all other systems and formats, and to remove stones from horses’ hooves.

But, and here’s the problem, it also replaces nothing at all as well as it could. There are maybe no more than half a dozen reasons why, but they are critical reasons and any one of these reasons will limit the use of the A7R.

- No in-body stabilisation and not all lenses are stabilised

- No electronic first curtain means the shutter cycle is noisy and causes vibration see later comments

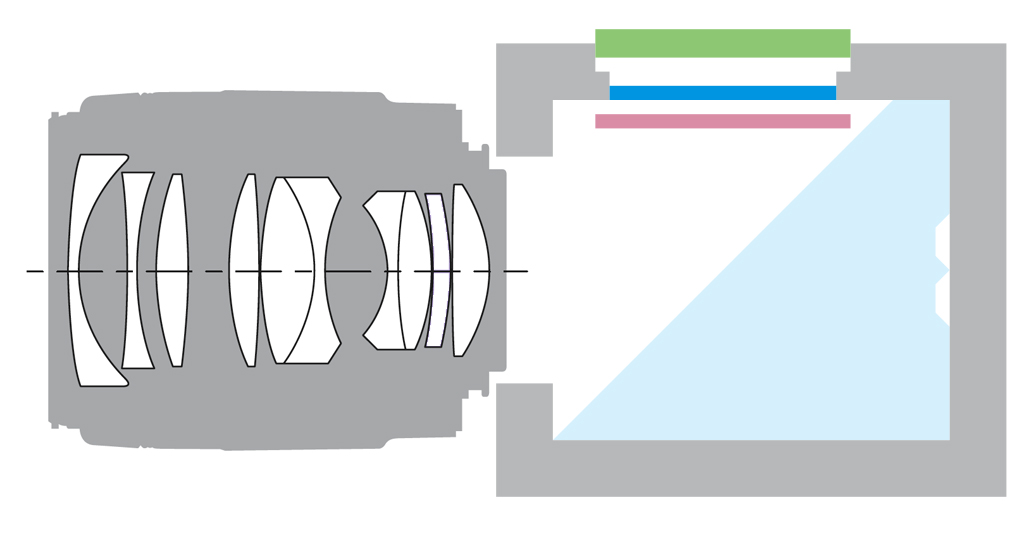

- The sensor design prevents optimum use of rangefinder type lenses under 35mm focal length

- No native full frame wide-angle lens under 24mm is likely to be available before September 2014

- Any Sony FE-mount lens with a performance matched to the sensor is going to cost double its true value

- No on-board GPS and (to date) no multi-function shoe GPS module to add

- Single card slot only and consumer size lith-ion battery

- Very slow start-up and wake up from sleep especially when not using Program, Manual or intelligent fully auto modes

- Slow optimal AF/AE performance continuous shooting

- Slow laminar shutter blade transit speed and flash synchronisation limit

- Firmware compatibility problems with some existing E-mount OSS lenses

- No provision for IPTC copyright information entry

- Custom lens app can be used with manual adapted lenses but does not embed metadata in EXIF

- User memory settings don’t cover functions from some menus

- Apps are charged at additional cost for functions which would reasonably be free or included in a camera body with a price-tag of £1,800

- No battery charger is supplied and default charging method is by micro USB cable

- The rear LCD screen can only be tilted and is not reversible to face the body

- The EVF even at its brightest is not up to tropical or desert viewing conditions

- Auto switching EVF to rear screen is unreliable

- As I have now found after five months’ use, not as durable as it looks (I have repaired the worn metal showing through the sharp edges on the ‘prism’ and body with a black Sharpie pen, but I’m tempted to use a guitar fret polishing sheet to make all the sharp edges into bright silver… just rub that thin black coating off!)

In case you’re thinking this is a completely unfair list of negative points to start a review with, well, you may be right. It’s here to make up for the usual lists of star features which *end* reviews. I’m also going to need to explain all these points. Here, to balance the negatives, are the positives.

- The highest resolution full-frame sensor (24 x 36mm) currently made

- The smallest full-frame system camera body

- No moving mirror, no SLT mirror, and no optical low-pass (anti-aliasing) filter

- 18mm lens mount register allows the use with adaptors of all current and past lenses from all systems designed to cover 24 x 36mm except those which used fixed rear assemblies and front groups

- Custom lens app allows corrections for any lens, while built-in function auto corrects E and FE mount lenses

- WiFi and Nearfield Connection transfer file to mobile devices or other hosts with automatic small JPEG creation even when full size JPEG or RAW is the selected shooting format

- Sony PlayMemories Mobile Apps downloadable to camera and devices add functions such as remote control and intervalometer, lens corrections, sensor shading and colour shift compensation

- The shutter is a professional specification speeded to 1/8,000th with motorized actuation

- The body is reasonably rugged, very light magnesium with some composite surface panels and is sealed against everyday dust and moisture ingress

- Although you can’t hear any sound, it has an Olympus-style ultrasonic vibration dust removal process and it is stunningly effective – no big buzz, no vibrational you can feel, but it really works

- A full set of buttons can be customised for functions, and there are three adjustment controllers plus a dedicated exposure compensation dial

- The electronic viewfinder with 2.3 million pixels and a 0.70X virtual view is only beaten by Fuji’s X-T1

- Triggered or manual magnified manual focus allows exceptional focusing accuracy when needed

- The high cost of Sony dedicated lenses is offset by the quality of many low-cost, older manual lenses and the option of two adaptors for Sony A-mount lenses, SLT mirror type or mirrorless

- The interface allows manual selection of most functions, including APS-C format crop or using full frame with non-FF lenses, movie audio gain, finder/screen exposure simulation, and lens corrections

This last point may seem a bit vague but it’s actually what makes the A7R usable at all in many circumstances. The APS-C crop on/off has saved the camera from having zero real wide-angle choice during its first three months of release, as our December 2013 article on the use of the Sony E 10-18mm lens showed.

Although electronic viewfinder cameras are not ideal for studio work, the high resolution of the A7R makes it an alternative to medium format for the highest quality. It can be set to ISO 50 or 100, with 14-bit raw files using a compression method which is comparable to Nikon’s lossless option. If ‘Setting Effect Off’ is selected, the EVF or screen will always show a bright auto white balanced image allowing modelling lights to be used for composing and focusing even when the actual shot will be taken by flash with a fixed preset WB. The professional or advanced user will want to have all the settings for such work stored as a custom memory preset, but Sony puts the ‘Setting Effect’ outside the saved functions. This is most frustrating as getting to it requires menu-diving.

The same applies to stabilisation, which is a function of the lenses not the camera. It is turned on or off through a menu setting or by assigning a Custom button for direct access, making occasional tripod work need an excursion into the menus before and after, unless you are to end up with OSS enabled or disabled inappropriately. The E/FE lenses have no OSS switch, the body has no switch, and there’s no one-press shortcut. Sony’s decision to omit M/AF and OSS on-off switches from the FE lenses makes the system just that little bit harder to work with. Buy a Canon or Nikon and even the cheapest lens has a stabilisation switch you can use easily every time you mount the camera on a tripod, work with flash, or use a fast shutter speed and want the optimum lens performance (achieved, almost invariably, with stabilisation off).

No in-body stabilisation is going to handle this anyway – luck, flash, a tripod or a very fast shutter speed provide the answers

Working speed

How much does ANY of this matter, if you simply fit the appropriate kit lens or prime, and just get out and use the camera? Not a great deal if you use the camera like a point-and-shoot and your objective is a small print or posting on Facebook. Given the remarks I’ve seen on-line from people buying an A7R with a view to catching their ‘toddler running around’, plenty of new owners fall into this category. They are lucky because no matter what camera they buy, from a £50 supermarket offer to a Canon EOS 1DX, they will be happy with the results and only criticise them when the family pet outpaces the autofocus in the ideal photographic conditions of their living room.

The main issue which will hit any user of the A7R is its overall operating response and speed. Acquiring focus, by contrast detection, normally seems to take around 1/4 second with an FE or E lens, but can take half to one second in low light or with a low contrast subject. It can also fail but confirm positive occasionally, and this is a little frustrating as we are not used to getting defocused snaps today. Even one fail in a hundred is a surprise. If you try the LA-EA3 adaptor, which provides a mirror-free light path and supports AF with SAM and SSM lenses, half to one second is normal in good light. You may find it worth disabling the ‘AF with shutter’ option and using only the AF button to set the focus, so the shutter release does not keep resetting it with each shot. However, after doing this I found it more than inconvenient NOT to have the familiar AF on half-pressure.

The shutter cycle

Having acquired focus, you complete the shutter release action. The A7R then executes a pre-exposure shutter action which involves closing the shutter with a movement of both blinds. This takes 250ms, or one-quarter of a second. That is longer than the mirror lift timing of a DSLR. After the exposure is made (a minimum period of about 6ms) there is short blackout dwell and the shutter re-opens to restore live view. The complete cycle is between 375 and 385ms as timed using audio and video recording and analysis.

This is not so very much worse overall than the Alpha 99 full frame SLT used with mechanical first curtain, but more of the cycle happens before the exposure, creating a surprisingly long shutter release lag. The A99, like the A77 and NEX-7, NEX-6, A6000 and indeed most other new Sony models including the A7, can use Electronic First Curtain. This means no mechanical action happens before the exposure at all. By the time you see any blackout or hear any noise, the image has already been captured, silently; the second shutter curtain closes to end the exposure and allow electronic readout. The shutter lag with an Alpha 99 or A7 in this mode is 20ms, or 1/50th. The shutter lag with the A7R can not be reduced to less than 1/4 in single shot mode.

This is also why the regular continuous shooting offers only 1.5fps, with AF and AE supported for each individual frame and 14-bit raw data. If you set Speed Priority mode, you can get between 4 and 5fps at the most with the exposure locked but AF active – however, you don’t get a real time viewfinder display, and you also get 12-bit recording instead of 14. This lowers JPEG quality in-camera as well as the headroom and dynamic range of the raw file. You’ll only get this performance by using the best SD cards. Some which claim 90-95Mbps speed only write are half or less, and are quoting their read speed.

The A7R will often remain in a card-writing state for several seconds (as long as 16 seconds if a raw sequence has been shot and buffering is queuing the images). Playback or review is not always possible without a brief wait. Since turning off auto review (which is not subject to this wait) greatly improves EVF performance for rapid fire shooting, you may have no clear idea of your shots until well after they are captured.

The simple fact is that where many competitors including Sony’s own A7 have fast responses, the A7R has an operating speed closer to a 1970s film SLR with ‘auto winder’ (the slow alternative to a motor drive), or being more charitable, to a Mamiya 645 with a power winder. It’s essentially medium format operating speed. This is in contrast to the Nikon D800/E, which offers the same file quality without a speed penalty.

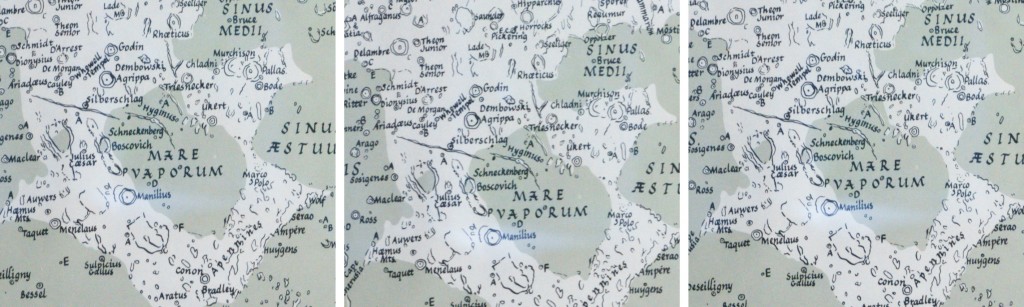

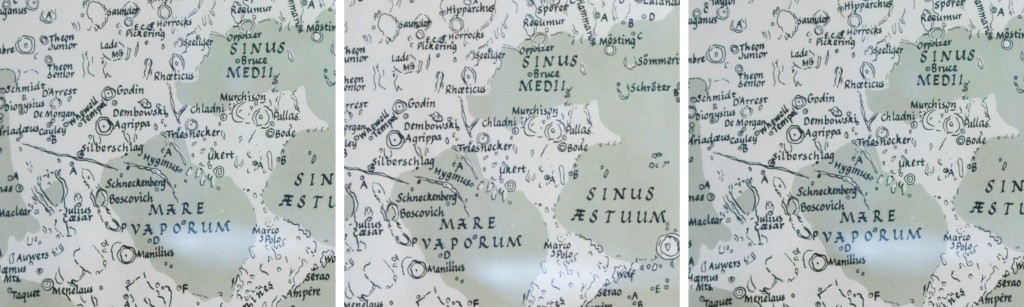

Sensor shading and lenses

The A7R sensor microlens and coating structure produces not only a strong magenta-purple shading towards the frame ends with short rear focus wide angle rangefinder lenses, it also throws up a yellow-orange discolouration at the top of the (horizontal) frame. It shows some degree of this effect with nearly all lenses under 40mm focal length made for Leica M, screw, Contax G or similar mounts.

A month after releasing the camera, Sony issued a PlayMemories App which can be loaded up and invoked to record and re-use manually adjusted corrections for named lenses. These include distortion (barrel or pincushion), vignetting, and colour shading. The app does not allow the creation of a reference image or mapping mask. You can do this for Lightroom (shading only, saved as data) or Capture One Pro (shading and colour, dust and defects saved as an image). Consequently it actually won’t correct properly as it ignores the yellow-orange patch. Its limits are insufficient to correct full fisheye to normal (as found in the onboard correction which Nikon use for their 10.5mm lens) or handle typical shading from lenses like the Voigtlander 12mm, 15mm and 21mm.

This is typical of a non-retrofocus wide angle shading map produced from the A7R. The slightly magenta vignetting can be cured easily. The piss-yellow patch can not and it’s there, to one degree or another, with more lenses than you would imagine.

A different aspect of the sensor construction produces smearing. I noticed that this was minimal with the 15mm Voigtlander and strong with the 21mm. It seems to depend on the rear group geometry relative to the sensor. I ended up selling both these lenses.

Since then, I have given up on the idea of a super-compact Leica style outfit though I still have a 40mm f/1.4 Voigtlander and an 85mm f/4 Zeiss. Sony’s FE lenses are not very small and not all that attractive in specification. They do little more than return me to the kind of lens choices I had thirty years with the launch of the Minolta AF system – a slight step backwards at the time, losing the 17mm f/4 option, 24mm VFC, 35mm VFC Shift, Varisoft and many other unique bits of glass. I’m using a bunch of vintage Pentax, Minolta, Canon and other lenses in the 17mm to 85mm range. They don’t suffer from sensor shading or smearing problems and have generally proved far better than modern zooms.

My gripe with these solutions is that even if I enter a lens identity in the App, my images show no focal length data in the EXIF info, and certainly no aperture data. At the end of a long day, I have not made notes on every change of lenses. I have no idea what lens or settings may have produced a good or bad result. What I need is for every lens to be a properly dedicated FE mount one whether AF or manual focus. And I don’t want to pay Carl Zeiss a thousand pounds to get a sharp result from the type of lens and aperture specification which has been easy to make to an outstanding performance level, at modest cost, for the last half-century.

There are three lenses made by Sigma – 19mm, 30mm and 60mm f/2.8 designs in E-mount – which prove it is possible to make low cost, lightweight lenses which deliver results almost beyond criticism. Just making the direct translation of these lenses to 28mm, 45mm and 90mm f/2.8 for (say) 50% extra cost would give the A7R exactly the kind of glass it needed from the launch day. Sony’s Carl Zeiss 35mm f/2.8 and 55mm f/1.8 may be wonderful in their own right but they appeal to me as much as 35mm f/2.8 lenses and 55mm f/1.8 lenses did back in the 1970s. Not at all. They are the focal lengths and apertures you used to find on twin-lens film compacts and they’re what you still find in the scruffiest old bag of 1960s worn-out SLR kit at a junk sale. They are what my father’s Pentax kit had (plus the inevitable 135mm).

Fuji’s launch of the X-series with a fast 28mm pancake equivalent (18mm f/2), very fast 50mm equivalent (35mm f/1.4), and good 90mm equivalent macro (60mm f/2.4) paid off well and they followed up with a 14mm f/2.8 (21mm equivalent) and pro portrait 56mm f/1.2. Though not cheap, these lenses are all affordable and have been supplemented by further excellent kit, tele and wide-angle zooms. What the A7/R needs most is a direct counterpart to this Fuji system and it simply doesn’t have it.

As for the long end, I see almost no point in buying any lens made for the FE mount longer than something like 100mm. The 70-200mm f/4 may be attractive, but it’s forever limited to the FE mount while being as long as a regular Alpha lens. Had Sony made a clever two-part SSM lens for FE and Alpha, with a detachable rear tube like a dedicated LA-EA3, they would have had a winner. Instead they have the lens which Alpha A-mount owners have been waiting for – pressing for ever since the digital system arrived – made in the new mirrorless mount only. After seeing the final prices of the CZ 24-70mm f/4 and the Sony 70-200mm f/4 G, I’ve bought an LE-EA4 Alpha SLT adaptor as well as an LE-EA3 mirror-free adaptor.

But longer lenses are still much better on the Alpha mount, with its sensor based stabilisation and the larger bodies with true phase detection AF ideally suited to the wildlife, action, news and sports for which lenses over 200mm are destined. You can add an LA-EA4 SLT type adaptor to the A7/R, but these are still full-frame cameras one of which (the A7) has extremely low resolution for tele work compared to the ultimate telephoto capture machine, the neglected Alpha 77 (or its lesser spec 24 megapixel siblings).

From my point of view I’ve got an amazing camera body with a few limitations, but a menagerie of odd lenses all with even greater limitations or lack of connectivity. If someone came out with a Canon FD lens adaptor with a chip able to tell the camera I was using a 20mm and what aperture was set, that would be great.

What does work is any LA-EA adaptor with Alpha lenses. You get all the EXIF data, and aperture control from the body. What you don’t get is the smooth focusing of a manual lens, or contrast detect AF, though you do have AF calibration to fix the inevitable inaccuracy of phase detect systems. It’s just a pity the 20mm Minolta/Sony AF design isn’t as good as the 1980s Canon last version manual focus FDn.

Timing and shake

The A7R shutter is a full size mechanism. A shutter like this running at 1/8,000th maximum speed should be achieving flash synchronisation at 1/250th. The fact that this camera is restricted to 1/160th shows that the transit speed of the shutter blinds is slower than normal. There must be a reason, and the discovery (by me, and others, despite vehement denials in some quarters) that a shock-induced form of camera shake happens could be it. Sony has also disabled OSS support for many E-mount lenses. I believe this is connected to the typical shake pattern in the hands of the average user. Update: because it occurs less with unstabilised lenses, for example my 70-210mm f/4 Minolta AF used on LA-EA4 shows none of the typical patterns, I now think this is not a ‘shutter shock’ or ‘user shake’ issue but is due either to mistimed communication between the camera and most stabilised lenes, or more likely, to a brief loss of the power needed to maintain moving lens groups or elements in position whether stabilisation is active or not. A need to moderate the drain on the battery is indicated by the slow transit of the curtains (slow motor speed to operate the shutter). Otherwise the A7R would surely have had a full speed 1/8000th shutter with X at 1/250th.

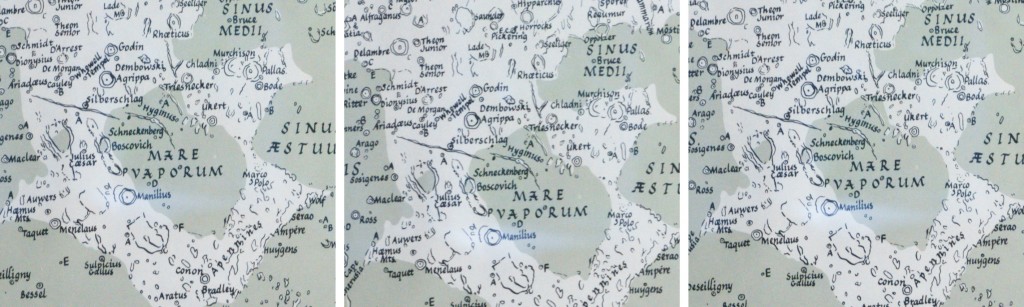

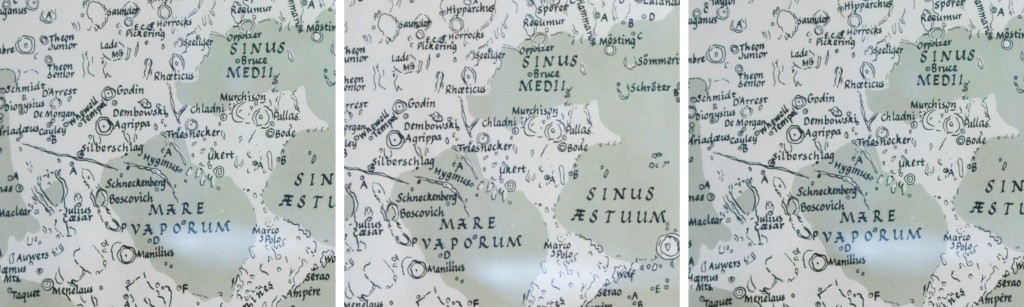

I made recordings using video, audio and motion sensing methods and observed the typical results from repeated exposures with different lenses. I found that shutter speeds from 1/30th to 1/160th could be affected by a shake or double image which occurs 1/250th after the shutter has opened, looking like a reflected or transmitted shock. At speeds longer than 1/60th this jolt occupies less than a quarter of the overall exposure and is not so clearly visible as a double image. It can look worse at 1/160th than 1/80th, because at 1/160th about half the exposure can be in one position and half with the image shifted a tiny degree. A distinct double image is often shown and it’s always in the vertical direction when the camera is held horizontally.

FE 28-70mm handheld 1/80th, OSS switched on (100% detail click to enlarge). Pre-update firmware. It’s very hard to be sure, but I think the April firmware update has made the 28-70mm (originally NOT recommended for the A7R or sold with the body) perform better.

FE 28-70mm handheld 1/80th, OSS switched off.

Sigma 70-300mm OS switched on, on LA-EA3 adaptor. One problem with using any non-Sony lenses is that firmware updates have no effect on them at all. Sony don’t make a stabilised lens going as long as 300mm, yet.

Sigma 70-300mm OS switched off. All images at 70mm (many tests made, these are accurate representations of the results and tend to show that stabilisation is likely to produce no benefit).

Since some stabilised lenses including my Tamron 18-200mm Di III VC also produced this distinctive double exposure, I believe that Sony’s disabling of OSS in the 55-210mm E lens for example was done because their engineers identified the problem before the camera went on sale. I also think it can be fixed by firmware updates to Sony E lenses, but probably not for others. Update: they did not update the new black 55-210mm OSS. I think it just imposes too much battery load without an entirely redesigned OSS mechanism, or perhaps a combination of OSS and focus. Fuji has overcome this problem using very carefully balance triple linear motors in their new large lens for the X-system, the 50-140mm f/2.8 – it’s a stabilised, fast focusing lens with minimum power consumption.

In response to those who say oh, it’s a super-high resolution camera, your technique needs to be (bla bla bla!) it’s actually slightly lower resolution than my NEX-5n and far lower than my Alpha 77 or the NEX-7 I no longer have. It’s also lower than the A3000 I owned briefly, and the NEX-6 I have used as a second camera since early March. 36 megapixels full frame is 15 megapixels APS-C and that’s a lower resolution than any E-mount camera made except the original NEX-5 and NEX-3 14 megapixel bodies. I can enable mechanical first shutter curtain on any other NEX or Alpha SLT body and never see the same ‘jolted exposure’ effect with the same lenses. I can also shoot with our Alpha 700, 900 and 580 bodies and never see this shake fingerprint despite their mirror mechanism and mechanical first curtain combined.

Of course I may get shake with disabled or absent stabilisation, hand-held, with almost any digital body. I use many different cameras through the year and sometimes I get very poor stabilisation, as when using certain Nikon lenses with the earlier VR zooms on their 24 megapixel DX format bodies. This shake is random and variable, and reflects my own instability, body sway, wind chill and so on. It’s not one type of shake visible too often in shots which should not normally be affected.

Reviewers have been incredibly cautious to observe this effect. I don’t know why. I’d spotted it within a few hours of trying the camera out. Others have been fast to defend the A7R and suggest that you just need to avoid that critical shutter speed range of 1/60th-1/160th. If this was not such an extremely useful speed range that would be fine. It’s actually the precise range you most want to be perfectly stabilised and least want to have to avoid. It’s also favoured by Sony when program mode and auto ISO are used.

One way to minimise this shake seems to be to use manual focus, mechanical lenses and to favour short focal lengths. The A7R never feels or handles better than when you’ve got a rangefinder lens in the range from 12mm to 28mm fitted. It becomes like the Leica that never was, the eye-level camera which doesn’t need a separate viewfinder to handle a 12mm, 15mm, 18mm, 21mm or 24mm lens. Leica may have a good rear screen to help with this issue now but no EVF. So the next point has been a big issue for buyers.

For the latest firmware updates, and new Apps and software, see:

http://www.sony.co.uk/support/en/product/ILCE-7R

And for the rest…

While I do miss the dual card slots of most of the Alpha cameras I’m using, I know the NEX and E-mount models have never had this, and with a 32GB card installed I have adapted to using the USB cable to read off new images and let the A7R charge. I do not miss the separate battery charger as I have one, and spare batteries. Nearly all the time, the camera is kept fully charged by its time spent overnight attached to the Mac. Since my RX100, RX10 and NEX-6 all work the same way using the same cable life has been simplified.

My favourite designs remain the A55, A77 and A99 all of which have had GPS on board and rear screens which enable self-filming for video demonstrations, or folding away to face the camera (how I normaly use EVF cameras now). The shared battery across the A55, A7R, NEX and A3000 models and RX10 makes it likely I might travel using a combination of these. I don’t have much use yet for the WiFi functions but I understand their importance to others, and they will really come in useful for remote camera operation in future. That can include skypole or kite work, or having a camera tripod mounted 10 metres away from the main shooting position for a different viewpoint of an event, operated from a phone or tablet.

GPS identified this as a church at Mailadumpara on the highway to Munnar – the 10-18mm lens used on full frame enabled this uncropped 36 megapixel shot at 14mm, f/11 (the shading is due to natural sky polarisation and the vignetting of the lens which I have not corrected).

I found a solution to my GPS problems in the form of a £40 igotU device from Maplin. It’s tiny (I am tempted to put a hot shoe mount on it but so far have just popped it in my shirt pocket). Free igotU2gpx file reading and low-cost PhotoLinker (buggy and unreliable in the extreme with 36 megapixel raw files) let me write GPS data into full day shoots on all cameras used. It’s not as accurate as built-in GPS and the process is tedious; the GPS data also exists in sidecar files until MediaPro is used to embed it into finished JPEGs. I’ll still buy the GPS module for the multi function shoe just as soon as Sony release it.

Top quality files

The appeal for me of the A7R is the sheer quality of the image. Even at ISO 3200, it is completely acceptable when processed carefully with Adobe software from raw. The JPEGs are mediocre with the exception of multi-shot modes and I don’t use them except for panoramas and night shots. The raw file has been criticised but compared directly with competitors, I find it has what I need – excellent highlight recovery from normal exposure levels, very low noise across a wide range of ISO, an ISO 50 setting ideal for studio lit subjects, and extreme pixel level sharpness.

The Lomography Petzval lens used on the A7R with Nikon adaptor. This reproduction lens from an 1840s design is a wonderful tool for portraits.

Richard Kilpatrick as a Victorian portrait subject with our Interfit background as a drape – A7R, ISO 50, Petzval lens at f/5.6 (Waterhouse stop) manually focused, Elinchrom Ranger Quadra RX flash.

Manual focusing with peaking and magnification combined tells you a lot about your lenses. Find a good lens, and the peaking will be present even at Low setting, with a very narrow band of activation. A poor lens (or aperture setting) usually fails to show a peaking line at Low setting, then shows one at Medium or High which has little discrimination. I’ve been able to identify my best manual and A-mount lenses by using the 14.4X magnification and the peaking function to examine targets.

Having done this, the extra performance squeezed out of almost lenses by super-accurate focusing makes AF seem inadequate. The contrast detection AF of the A7R is good, but just invoking magnified manual after it has locked on proves that it rarely hits the perfect mark. It gets to ‘good enough’. Like many new A7R owners, I find myself often using manual focusing without noticing that it is any slower than AF used to be. It’s a quantum leap ahead of any optical finder accuracy.

I find the body shape and size ideal, and have no complaints about the position of anything except the shutter release, which could have been 3mm or so further forward, and also would have been improved by the addition of a manual cable release thread (found on the RX10). I don’t plan to get a vertical grip, as the whole point of the A7R is small size and light weight. The external finish feels secure, the battery and other doors are adequately sealed and I don’t tend to overwork them.

The small body size causes a few problems with tripod mounting. Even the smallest monopod head can restrict the rear screen movement making it impossible to angle the screen down if you want to hold the camera above head height. It doesn’t angle down much to start with. The position of the Menu button, needed to access some adjustments like OSS and Finder Setting Effect, isn’t ideal as the only button on the left end of the camera. The exposure compensation dial is unusual as a solus function using up an entire large mechanical control, and has no lock, so it can be turned a little easily.

The A7/R is so customisable that after a couple of months getting used to it and changing things you’ll have a camera as far removed from its out of the box settings as a typical Canon ends up. Mine, for example, has the AF/MF and AE Lock button/switch control set up to act as Focus when set to AF/MF (with pre-Focus and tracking lock and eye-start focus all disabled), and to act as Focus Magnifier when set to AE; while the shutter release is set not to activate AF, but to lock AE on first pressure (when using the camera in a controlled environment – when travelling, I soon reverted to AF with shutter). This makes the camera anything but point and shoot, as out of focus shots are guaranteed without a separate focus action.

In practice

Like far too many A7R users, I’ve spent half my time testing and experimenting, and not enough time shooting. I’ve had the RX10 as a companion at the same time, and needed to shoot with new flash systems, where that camera’s exceptional high speed sync makes it more versatile – there’s not much point having flash heads which manage 1/5000th duration when your sync speed is 1/160th, unlike the RX10 which can manage between 1/1600th and 1/3200th depending on aperture. I had a concert venue opening to shoot, with video, and once again the silent RX10 with its superb video quality was the obvious choice.

Then, at Easter, we had a nine-day tour of Kerala, an exceptional offer from Citrus Holidays providing us with a private driver and a packed itinerary covering 1000km and five locations. This was our first visit to India for 28 years, and would provide the first library images of India apart from a few scanned transparencies of subjects which do not date. Equipment mattered. Shirley always uses her Alpha 580 with Sigma 18-250mm OS original version; it’s heavy and the lens has been through one factory service already, but it’s been very reliable and survived a short period where a Nikon D600 kit was tried as a replacement (and sold pretty sharply, in favour of returning to the more reliable AF, AE and clean sensor of 580).

Logically, my A77 and A55 would have come along. They share the same battery type, and my basic lens set 8-16mm, 16-80mm and 70-300mm gives both exceptional wide angle and a good tele performance (300mm plus APS-C plus 24 megapixels) for wildlife. It is however a very heavy kit and we wanted to travel light and work light, in high temperature and humidity.

So, the A7R had to be my choice. Apart from anything else, this camera at £1800 had not so far proved ‘better’ for any given job – it was barely used. In the studio our A900 and A700 optical finders just work far better than any EVF camera, and for general PR and social photography the last thing you need is 36 megapixel full frame. It just creates oversized files and tends to have too little depth of field. The A7R had been used for tests, for some winter landscapes, and some architectural shots. We had not travelled at all since early November.

This decision also led me to leave the RX10 behind, and this was a big mistake. I took the RX100 instead because the RX10 is fairly large. Its zoom range and silent operation would both have been valuable. With the A7R and its 28-70mm OSS lens I took the 10-18mm OSS, my Tamron 18-200mm VC DiIII, NEX-6 body and 16-50mm OSS collapsible kit lens. This was really a backup in case any fault developed. In practice the A7R makes a better APS-C camera. I only used the 28-70mm lens once, and used the wide zoom and the Tamron fairly often on the A7R with APS-C crop, occasionally with crop disabled. While it’s possible to get a bit more wide-angle from the 10-18mm by shooting full fame, the 15 megapixel crop is a 100% perfect frame every time with this lens.

Despite the phase-detect focus of the NEX-6, this camera proved less accurate and slower in all conditions. Its main benefit was better timing for shots once the finder image is focused and stable, along with quieter operation. It may be a smaller body nominally but there’s little practical difference. Also, I was wearing a baseball cap, the minimum headgear needed in the sun. The left-end viewfinder eye position prevented a right hand ‘on top’ vertical grip on the NEX-6 while the central eyepiece of the A7R allowed a choice of grip style without having to remove the peaked cap.

The most significant loss my choice involved was telephoto power. Shirley’s 250mm f/6.3 reach on APS-C would have demanded a huge lens, a true 375mm or in practice a 400mm, to get the full benefit of 36 megapixels on full frame. It would also have demanded at least one f-stop more stopping down to match the critical long lens depth of field. I didn’t have an E-mount 24 megapixel body, but if I had one my 18-200mm would have slightly outreached Shirley’s 250mm as used on 16 megapixels.

This snake bird (anhinga) was photographed using the NEX-6 and 18-200mm (162mm and f/8), from a moving boat. There is no trace of shake at 1/250th, indicating the VC stabilisation works on this body. I got excellent results from the NEX-6, which I picked up at The Photography Show on March 4th with its 16-50mm collapsible motorized zoom on a special deal. However that deal was not as good as the current B+H of $524 with free accessories.

There are no lenses yet made longer than 200mm for the FE mount. If there are any made other than an obligatory zoom to 300mm they will be expensive and limited to the E-mount system for ever. In contrast a Canon, Nikon or Alpha SSM long lens will always be usable on SLR-form bodies and also on mirrorless – possibly on various mirrorless systems. Canon EF lenses for example can be used on almost all mirrorless bodies, and Nikon teles have the possibility of fitting to their 1 system 2.7X factor bodies with totally successful functions and focusing. I’ve tried this and it works – an 800mm equivalent with outstanding image quality, from a 300mm.

It’s for these reasons I have succumbed to ordering an LA-EA4. I value the LA-EA3 because it allows me to use some lenses with contrast detect focus and a pure image path, but my favourite 70-300mm Sigma OS will not CD focus. Buy the EA4, and I can use all my screw drive Minolta and Sony glass.

This is why I sill feel the A7R can be described as the Swiss Army Knife! It can do APS-C as well as its 16 megapixel APS-C siblings, but switch to use full frame to squeeze extra angle from many lenses. My Tamron 18-200mm is only just compatible with the A7R – its VC stabilisation and general performance indicate that a firmware fix might be needed (see earlier comments) – but it can give me a 19 megapixel image sharp corner to corner with a range of image sizes from square to 35mm, at 18mm and f/11, making it as useful as a 16-200mm lens instead of an 18-200mm.

In March, I needed to write up the Samyang 24mm Tilt-Shift lens, which was only available for review in Nikon mount, and needed a full frame body. The A7R with a low-cost Nikon adaptor did the job perfectly and the magnified focusing function allowed full and successful use of the lens functions. I now have a wide range of lenses and adaptors, and there’s no manual lens I own which the A7R can not use.

The Samyang 24mm Tilt-Shift f/3.5 manual lens has better control over movements (including 30° intervals for independent rotation) than the Canon or Nikon in the same focal length, though it lacks auto iris, EXIF data and focus confirmation. Here it is used with a low-cost manual Nikon adaptor.

Using the 24mm Tilt-Shift – a lesson here in floor/ground and ceiling/roof relationships and camera position. First shot, a typical eye level architectural compromise in which a normal wide angle keeps the verticals straight. The trade-off is that you get a similarly generous view of both the floor and ceiling. Second shot, moving the camera close to ground level. Third shot, applying a full vertical shift; the floor is now seen from an angle giving it much less emphasis, while the vaulted roof is seen from below. For real estate shots, the camera is usually placed close to the ceiling on a tall tripod, and a drop front applied, to show the extent of room interiors better by emphasising their floor area. This is stuff I learned 40 years ago working with 5 x 4.

The A7R stabilisation incompatibilty issue with the Tamron 18-200mm was ‘tested’ at considerable cost in lost shots. During most of the Kerala trip, fortunately including a few chances to get close to wildlife like the anhinger shown above, I used the 18-200mm on the NEX-6 for the slightly higher resolution and faster response. I’m very glad I did this and put the A7R away. No shot shows any sign of stabilisation failure. Finding a dramatic sunset location with rocks and predictable spray from breaking waves, I used the same lens on the A7R, which I had taken to the beach to produce some tests showing full frame coverage.

One of my frame coverage tests of the 18-200mm on the A7R. 175mm, 1/200th at f/9 – conditions which with stabilisation should result in a perfectly sharp result almost every time. Instead, this combination produced a jerked slightly double imaged unsharp shot every single time. Even at 21mm focal length this degradation was visible.

All the images (full frame tests and rock sunset shots) showed the same characteristic stabilisation jerk even at 1/320th, which I had not considered possible as the peak vibration from the A7R shutter occurs 1/250th after the shutter opens. It may not be shutter shock which causes this shake effect, but a firmware incompatibility (in timing signals?) between the A7R body and certain lenses.

Here is my processed image put through the new software Piccure, which I can recommend as the first program to analyse and remove shake effectively – see http://intelligentimagingsolutions.com – and which has significantly improved some of my A7R ‘shaken up’ shots to the point that when reduced to 9 megapixels, they are as sharp as you would have expected from a KM Dimage A2 (ah, the irony… we do make progress, don’t we?). Click the above image for a full size screen shot.

This was my final crop and process from the shot involved, which was an 18.2 megapixel ‘more than APS-C’ crop from the full A7R frame, sharpened using Piccure and reduced to 24MB final image size.

This sunset, and all the similar shots taken with the 18-200mm on the A7R, proved too badly affected by stabilisation malfunction to use at the desired full size.

Again, Sony’s decision to disable OSS with many lenses on the A7R only, and to issue firmware updates to enable this, supports this theory. Whatever the case, I lost all my first night’s sunset shots for anything except web sized use (above – it’s not sharp for printing or library use). We returned two further nights at the right time and tried various combinations. It was a subject not helped by heat haze and blown salt spray (UV filters were fitted, of course, and needed cleaning frequently to avoid the whole picture being softened).

It’s so bad it almost hurts your eyes, but this was the focus point of many shots, and the double image (always in the vertical direction when the A7R was held horizontally) from the 18-200mm Tamron consistently gave a result like this. You might also suspect inaccurate focus and poor lens performance, but plenty of other shots at similar apertures and settings on the NEX-6 were completely OK. Perhaps the only answer with the A7R will be the near-£1,000 70-200mm f/4 G and replacement of the 28-70mm with another £1,000-worth of 24-70mm f/4. All that to get me back to where I was thirty years ago in terms of aperture and focal length range!

Using Piccure had no useful effect on this shot. It created triple outlines of the shake in place of double.

Eventually I got what I wanted but only with the 70mm reach of the 28-70mm OSS lens. The final, third, visit had cloud cover as the sun reached the right position. But, if you want to try this for yourself, visit Light House Beach in Kovalam at around 6.00pm (get a beer and wait) around April 16th-22nd. Like all such sunsets, there are just two times each year where the sun will hit the right position over the horizon.

The 28-70mm really didn’t have the power to give me the sun at the size I wanted, but at least with Photoshop processing this was a more or less acceptable result. For any shot like this, I would far prefer to have a true mirrorless camera – no SLT mirror either – and the A7R should be a perfect choice. Tripod use was not an option because of the crowds (which you can’t see) and combination of incoming tide and wave.

There was one lens which never let me down – the 10-18mm OSS. Whether on the NEX-6, A7R crop or A7R full frame this lens always turned in a perfectly focused and well stabilised result.

At the end of our Keralan tour, we were invited to have lunch and a short tour of a major ayurvedic resort hotel, Isola di Cocco. The tour only took twenty minutes, seeing some of the rooms, and was at mid-day when the light is not ideal. I took a few shots on the A7R including room interiors, and sent small versions to our hosts afterwards. The outcome was a request for commercial use of the image set in their next brochure. These were not exactly what we would do on a commission – for one thing, we’d normally remove towels from round the pool, pick the best time of day, make fine adjustments to room details and even use lighting.

A pool needs to be very clean to handle a shot from three inches above the water surface (at 10mm).

This is what we we used to do in the 1980s producing brochure pictures for travel operators and it was never a casual thing, more a very long and full working day with many appointments and too much driving. These shots were quick snaps, even if professional snaps, and we agreed to use for a charity donation (all Indian businesses seem to support local charities as a matter of routine).

We’d be more than happy to go back and do it properly though!

Back in the 1980s we had nothing to approach the 15mm equivalent angle of the 10mm used on crop frame A7R, even though a few such lenses did exist for 35mm systems. 35mm was like using a 6 megapixel camera, and our shots had to stand full page to double page use. I used a Pentax 6 x 7 with its widest non-fisheye 45mm lens and that was equal to a 24mm, something you can now find at the wide end of many compacts. It had to go on a tripod, as the exposure times with Fujichrome RF 50 film (for shadow detail) with the f/16 or f/22 apertures needed for sharpness in depth were usually around 1/4 to 1 second. The tripod was one you couldn’t easily take by air today, and the camera kit with two bodies and three lenses was heavy and bulky. Then there was a matter of a hundred or so rolls of film to handle the five bracketed exposures for each frame, lead anti-X-ray bags, and a large Metz flash with an extension head… and our 35mm Minolta kit on top of it all. Each room could take an hour or more to photograph.

Raw conversion controls enable the rich teak wood interior to be shown clearly without losing the highlights of the wall and white sheets.

And here I am today, complaining about aspects of the A7R when I can walk into a room like the one above, without a tripod, find my viewpoint, observe the horizon level display while composing carefully, and make an exposure at ISO 1600 with quality equivalent to ISO 100 35mm film. With a lightweight carbon-fibre tripod, this almost Leica-sized camera can now outperform anything we might have expected from 6 x 7 film and at ISO 50 is good enough for wall-sized prints and poster reproduction.

We have some aspects of A7R technique and performance to ‘fix’ and you’ll realise that I do not approach using any new camera uncritically. But there’s nothing else on the market short of medium format which can match what it does.

I do not address, here, the demands of users wanting to switch from conventional heavy-duty SLR type cameras whose gear includes fast long apo telephotos and zooms, who work frequently with sequence bursts, require to track sports action, shoot news, capture wildlife or want to snap their kids and pets (which requires much the same camera performance as covering sports and news… they may move slower but they are much closer!).

My present thinking is that the new 12 megapixel A7S with its 4K motion picture capture and extreme low-light performance may not be what I want, but I’m considering adding an A7 or changing the NEX-6 for an A6000. I’m not quite ready to sell the A900 or the A77. I’ll see how the A7R performs over the summer and update in due course.

The A7 MkII with full-frame stabilisation, announced in November 2014, tends to put my theory about power drain and lenses into doubt, but only because I might assume the 5-axis sensor stabilisation also puts a heavy load on the battery. It does have the different shutter mechanism found on the A7, and of course, it does not have a 36 megapixel sensor to power.

– David Kilpatrick