If they want to fake a Mars colony story, a video version of British software developer Anthropics’ LandscapePro could be useful. It’s from the same team who created PortraitPro, and it allows you to change almost any landscape beyond recognition. It also allows subtle and careful modifications, or essential commercial fixes like a better sky in place of blank white.

One September weekend, a visit to a local restored mansion and park (The Haining, Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders) was rewarding because the Moving Image Makers’ Collective had video art installations running in the house.

Above is a film with dual projectors using the corner of a room (by Jason Moyes, with power making its way from hydro-electric dams to lonely wires and pylons).

Outside things were not as inspiring.

Of course the components of a closer shot, using the ‘quay’ as a foreground, perhaps in black and white, are there. But from this view as I walked past, not really photogenic.

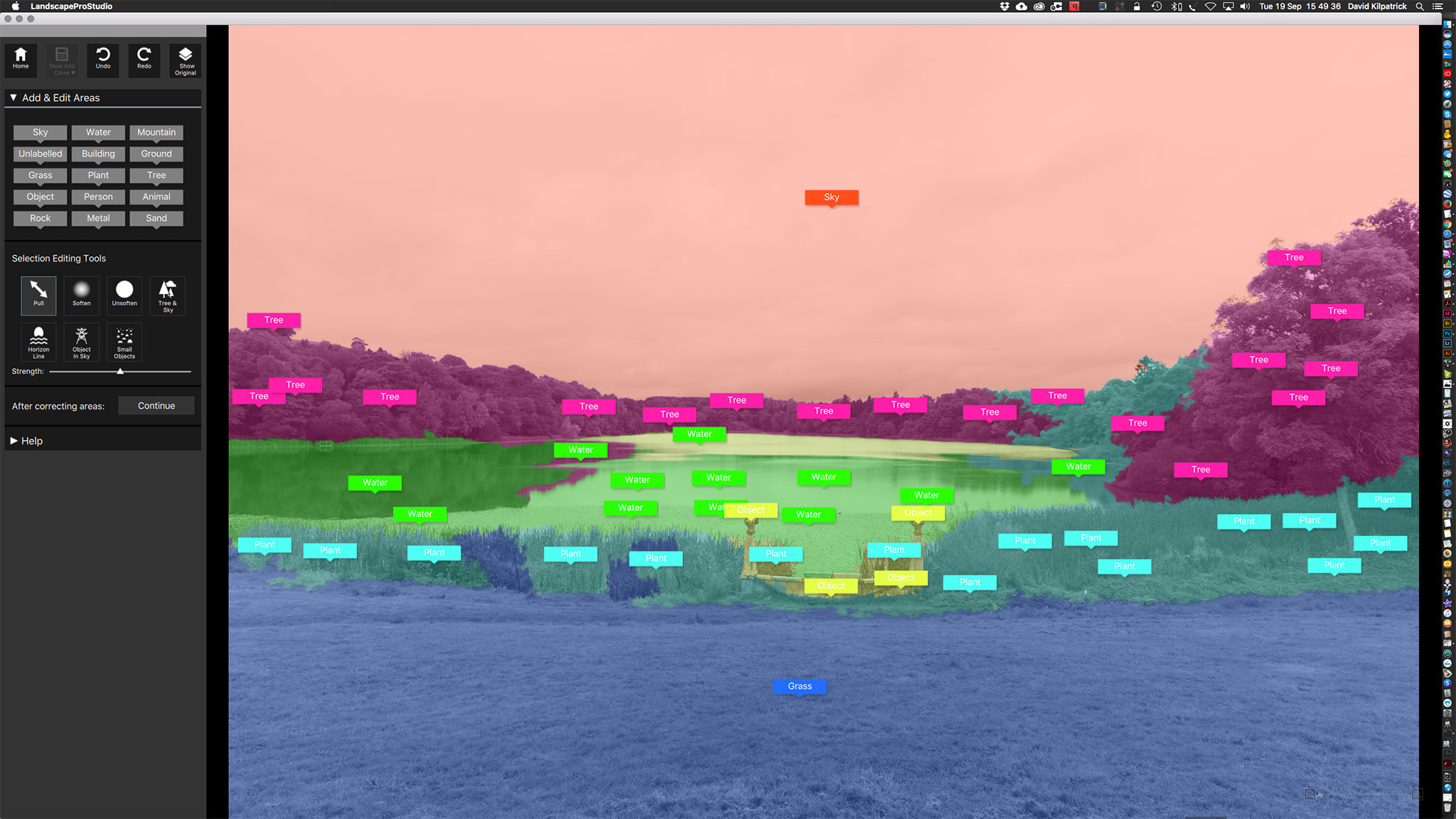

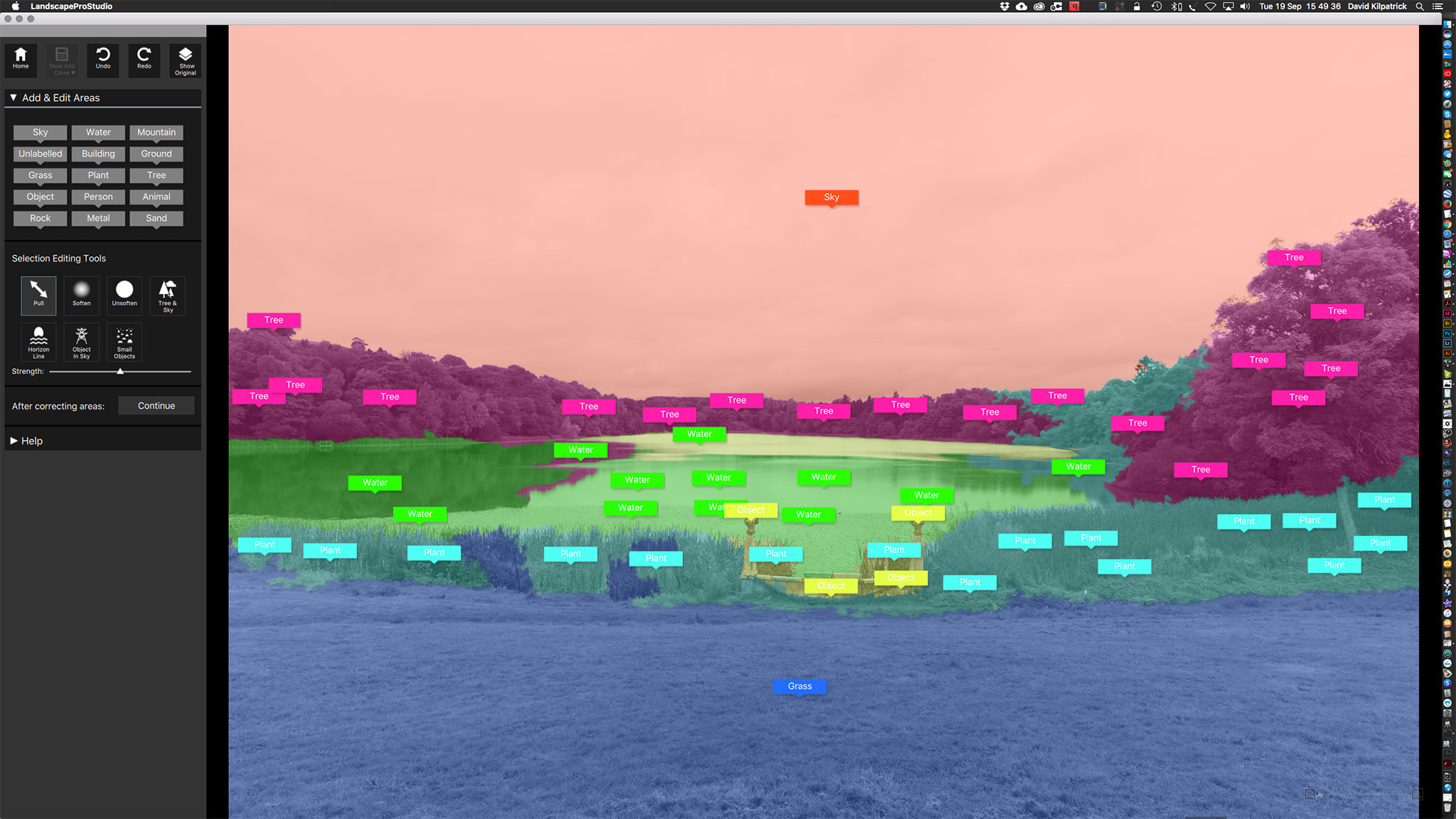

Here’s where LandscapePro can perform any number of tricks, some familiar from sets of actions or presets like a sepia vignetted contrast-boosted vintage look. But it’s the tools which let you mask off different areas, named in the control menus, that give the program (whether plug-in or stand alone studio edition) its power.

This is a screen shot during progress of auto-painting the masks by dragging the named tags on to various parts of the image. You can then refine them by expanding any part. It’s pretty difficult to mask complex tree horizons as on the right, and some post-process work in Photoshop may be needed. My not-serious rework here is a quick job. You could spend an hour or two setting up the masks for an important image. Even so, the program handles a Sony A7RII 42 megapixel JPEG well enough and most actions are as fast as you can shift the cursor

My idea here was make the scene look like a frosty morning sunrise. The sky is one of my other shots, not a LandscapePro stock sky (the program comes with a good selection but I prefer to keep all parts of an image my own work). The post-pro includes a method for getting rid of a white outline on the woods – you use the Healing Brush tool in Photoshop, set it to Darken, choose a source point in the sky above the horizon, and paint. A similar technique using the Brush tool set to darken with a sampled colour from the lake fixes original tones showing between the reeds. I find the Clone, Brush and Healing Brush tools very useful when combined with Darken or Lighten and controlled flow; I don’t retouch using Layers but have always worked ‘fast and clever’ on the background (single layer), after doing most of the image control and adjustments in Adobe Camera Raw which gives me an .XML sidecar saved non-destructive edit as complex as I need. Mostly, I don’t have to retouch at all in Photoshop. Both PortraitPro and LandscapePro suit me well as they are very fast to use and non-destructive; generally, you can’t see they have been used, especially PortraitPro, because I only use it when needed and then pick specific controls. It is easy to go over the top with these programs as this example shows, but this does not detract from their serious value for careful work.

For this image I also copied the sunset/rise area, flipped it vertically, and used the Clone tool to overpaint from the flipped version down into the lake to give a reflected sun glow. Colour changes have also been made to the trees.

Above you can see, close up, a detailed section with the original top and the processed version bottom. This should demonstrate that the program is not just a gimmick. I used to work with UltiMatte, Mask Pro and other programs which allow painted masking but the multiple different mask zones of LandscapePro take this a step further. Needless to say it’s a godsend for architectural photographers as the clean edges in most architectural shots allow rapid perfect masking and then each face of a building, ground area, sky and landscaping can be adjusted separately. You can work from raw files or from open images in Photoshop (as I did here – it’s not really a JPEG until saved).

You can try LandscapePro at www.landscapepro.pics, and get a 10% discount by using the coupon code F278. If you want to try Anthropics’ PortraitPro visit www.portraitprofessional.com, again we have a discount code – F2910.

UPDATE: August 2020 – until August 17th, use code CC8B on current 50% off deals to get a further 20% off any edition or upgrade of both programs. Visit this link.

– David Kilpatrick